A Woman’s Eye: How Imogen Cunningham broke through gender barriers to help redefine modern photography

posted Friday, August 23, 2013 at 10:16 AM EDT

"So many people dislike themselves so thoroughly that they never see any reproduction of themselves that suits. None of us is born with the right face. It's a tough job being a portrait photographer." -- Imogen Cunningham

In her long life, Imogen Cunningham was one of America's finest photographers and one of a handful of our great portrait artists. In a career that spanned nearly 70 years she worked in almost every area of photography imaginable and in a variety of photographic styles, from soft-focus Pictorialism to sharp edge modernism. She shot everything that, as she said, "could be exposed to light." Her portraiture was sought after by the rich and famous, and her images were widely published.

Throughout her long photographic life one thing remained constant: She photographed the world with a woman's eye, from a viewpoint far different than that of the male dominated photographic world of her time and ours. Cunningham was a true original and an essential part of the development of modern photography in America. And all her life she fought against a glass (plate) ceiling and she never gave up.

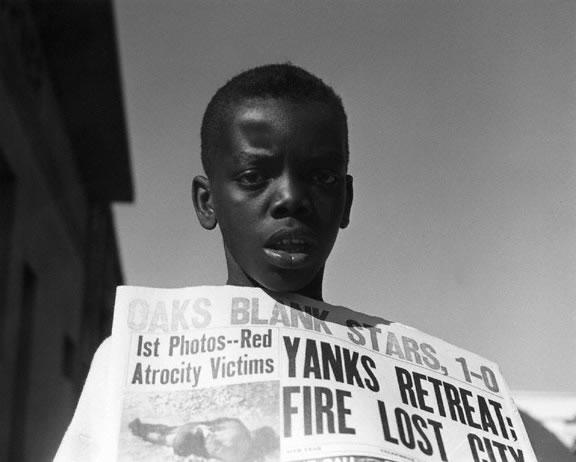

Boy selling newspapers, 1950

Photo by Imogen Cunningham, courtesy of the Imogen Cunningham Trust

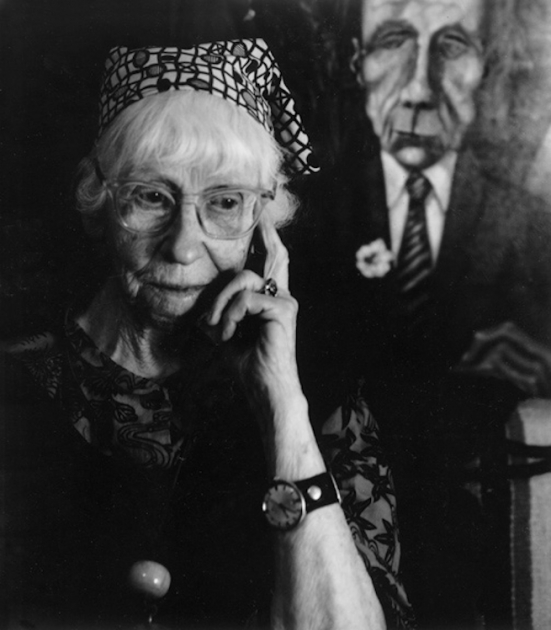

I was lucky to meet Imogen when she had come to Seattle in 1973 for an exhibition of her photographs. She was 90 years old at the time, a small woman who dressed smartly for a "little old lady." She wore a long ankle length skirt and colorful, embroidered peasant vest, and her white hair neatly was coiled into a bun under an embroidered cap. But when she spoke she was nothing like any little old lady I had ever met. She was funny and lively and peppered her conversation with a variety of four-letter words. I fell in love with her on the spot.

Independent and self-reliant

Born in Portland, Oregon, on April 12, 1883, Imogen was just 6 years old when her parents moved to Seattle. At that time the city was hardly a city, but rather a port and the gateway to Alaska and Yukon gold fields -- very much part of the "last frontier" of America. Her parents were no-nonsense, hard-working people who bought land and built a home and raised their daughter to be independent and self-reliant.

Imogen purchased her first camera when she was 18 years old. It was a $15 mail-order kit that consisted of a wooden 4x5-inch format camera with a rapid rectilinear lens and a set of glass plates. Though she taught herself how to use the camera, she wasn't completely bitten by the photography bug. She instead decided to attend the University of Washington to study chemistry and botany.

Marsh at Dawn, 1905-06

Photo by Imogen Cunningham, courtesy of the Imogen Cunningham Trust

During her senior year, as she was writing her thesis on photographic processes, she discovered the photographs of Gertrude Kasebier -- arguably the mother of modern American photography. She decided on the spot to become a photographer in earnest. Upon graduation, she talked herself into a sweet job as a darkroom assistant in the Seattle studio of Edward S. Curtis, a photographer famous for his photography of North American Indians.

However, lab work quickly bored Imogen and she decided to do something unheard of in her day -- she went off alone to Germany to study photography. She spent a year at the Technische Hochschule in Dresden and returned home in 1910, where she opened her own portrait studio and became one of the first female professional photographers in America.

Bohemian controversy

Imogen was wooed by Roi Partridge, a Seattle artist and printmaker. The couple were what was called in those day "Bohemians," free spirits who were more concerned with art than commerce. As if to prove this, one day they climbed up to the Alpine wild flower fields on Mt. Rainier and -- despite freezing temperatures -- took off all their clothes. Roi posed for Imogen as a mystical woodland faun. In one picture he appears to be magically standing on top of the water in a lake, when actually he was barefooted on a small floe of ice. After returning home, several of these photographs were printed in a Seattle newspaper, the upscale and arty Town Crier. Her images caused a scandal, one that centered on Imogen because it was unheard of at the time for a woman to photograph a nude man. (Although the opposite practice was quite acceptable.)

Roi Partridge on Mt. Rainier, 1914

Photo by Imogen Cunningham, courtesy of the Imogen Cunningham Trust

"A critic on another paper wrote a very harsh criticism -- a terrific tirade on my stuff as being very vulgar," Imogen said about the incident. "It didn't make a single bit of difference in my business. Nobody thought worse of me." Imogen was right. In 1914, her photographic efforts were rewarded with one-woman exhibitions at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences and at the Portland Art Museum.

Besides the nude shots of Roi, Imogen often took nude self-portraits, something she did throughout her life -- although as she got older she more often appeared clothed than not. As her granddaughter Meg Partridge, director of the Imogen Cunningham Trust said: "Her self-portraits really show her sense of humor, and she was smart about her career. She actively published her work in magazines and newspapers. She had a good eye, but she was a great editor. She knew how to edit her work, so what the world sees is an impressive selection of work."

Self portrait, 1910

Photo by Imogen Cunningham, courtesy of the Imogen Cunningham Trust

Imogen married Roi in 1915, and months later gave birth to her first son, Gryffyd before the family soon moved to California, where Roi accepted a faculty position at Mills College. She later had twin sons, Padraic and Rondal. While Roi taught, Imogen was a stay-at-home mom. To keep her passion for photography alive, she photographed her kids and the plants in her garden.

"The reason during the [1920s] that I photographed plants was that I had three children under the age of 4 to take care of, so I was cooped up," Imogen said. "I had a garden available and I photographed them indoors. Later when I was free I did other things."

Aloe shoots, 1920s

Photo by Imogen Cunningham, courtesy of the Imogen Cunningham Trust

Once free, Imogen spent her time taking pictures of a wide range of subjects -- industrial scenes, more nudes, more plants and more portraits.

Group f/64 and a commitment to "pure" photography

But at this time, America was facing the Great Depression, and in San Francisco a loosely affiliated connected group of photographers began discussing how they could create a new, more relevant, more meaningful kind of American photography to capture the reality of the world around them.

The outcome of these discussions was that Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, Willard Van Dyke, Imogen and several others founded Group f/64 in 1932. Rejecting what they perceived as the dominant "soft-focus pictorial" style they proposed a modern style of "pure or straight photography" to meet the challenges of the day. In other words, good-bye hand-colored, soft-focus, lyrical pictures, and hello to hard-edged, real-world ones.

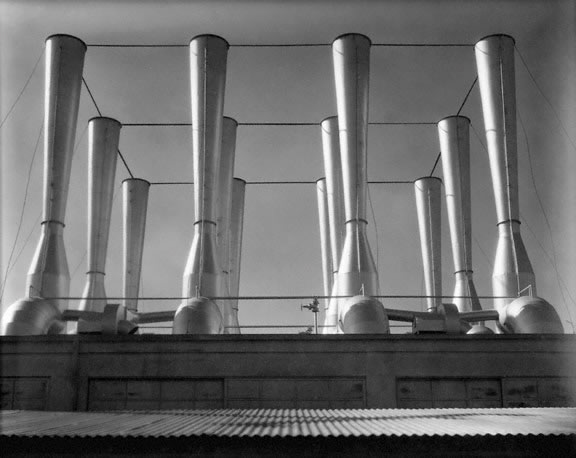

Fageol Ventilators, 1934

Photo by Imogen Cunningham, courtesy of the Imogen Cunningham Trust

They chose the name Group f/64 to reflect their commitment to these sharp, deeply focused images. Ironically, most of the group -- including Imogen and Adams -- had worked in the soft-focus style earlier in their careers. Moreover, in "creating" this approach they obfuscated the fact that dozens of American and foreign photographers had always worked in sharp focus. That included everyone from Timothy O'Sullivan to Eugéne Atget to Charles C. Ebbets.

While Group f/64 gave many photographers a chance to have their work seen for the first time, Imogen was already a established artist and she was restless by nature. So despite the acclaim she received for her botanical images, she explored other areas of photography.

"Ansel once said to somebody that I was versatile, but what he really meant was that I jump around," Imogen said. "I'm never satisfied staying in one spot very long, I couldn't stay with the mountains and I couldn't stay with the trees and I couldn't stay with the rivers. But I can always stay with people, because they really are different."

The call of Hollywood

Around this time her portrait work attracted the attention of the editors of Vanity Fair and in 1932 they assigned her to photograph the movies stars of the day—without makeup. "I was invited to photograph Hollywood," Imogen said. "They asked me what I would like to photograph. I said, Ugly men."

Among the ugly men she photographed were actors Cary Grant, James Cagney and Spencer Tracy. The only truly "ugly" man she photographed was Wallace Beery.

Spencer Tracy, on location, 1932

Photo by Imogen Cunningham, courtesy of the Imogen Cunningham Trust

In 1934, Vanity Fair asked her to come to New York for some work and she was all ready to go. But Roi opposed it, demanding that she wait until he was able to go with her. She refused and left for New York by herself. There had long been tensions between them, their careers pulling them in different directions, and soon after the New York trip they divorced.

A lifelong friendship with Ansel

Imogen and Ansel Adams had become friends well before Group f/64, and it was a friendship that would continue all their lives. But they were an odd couple. He was formal, reserved and conservative while she was blunt, a free spirit and a radical.

"There are certain things you don't discuss with Ansel, especially if you don't agree," Imogen said.

Ansel Adams, 1953

Photo by Imogen Cunningham,

courtesy of the Imogen Cunningham Trust

However, despite a lot of disagreements, they remained close, and in 1945 Ansel asked Imogen to join him on the faculty of the art photography department of the California School of Fine Arts (along with Dorothea Lange and Minor White). She accepted the offer although she had definitely un-Adams ideas about teaching photography.

"I don't think there's any such thing as teaching people photography, other than influencing them a little," she said. "People have to be their own learners. They have to have a certain talent."

Portrait photographer and feminist

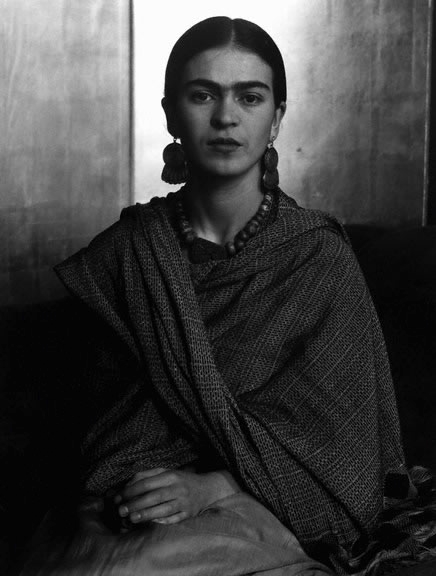

At her core Imogen was a portrait artist, and over the years she produced a pictorial Who's Who of modern 20th century art and photography. She made portraits of artists, musicians, dancers, and photographers -- everyone from Alfred Steiglitz to Frida Kahlo to Martha Graham to Brassai to the German photographer August Sander, and of course American photographers like Adams, Weston and Dorothea Lange.

"The fascinating thing about portraiture is that nobody is alike," Imogen said.

Frida Kahlo

Photo by Imogen Cunningham,

courtesy of the Imogen Cunningham Trust

She was an early feminist who despaired of the way women were treated and especially in the world of the arts. In 1922, when she went to visit and photograph Edward Weston, she arrived to find Weston and his current lover and model Margrethe Mather waiting for her. Although Weston was married, and the father of several children, he had a string of affairs -- which his then wife Flora appeared to tolerate. Now largely forgotten, Mather was also a photographer who had helped Weston move away from soft focus photography.

Edward Weston and Margrethe Mather

Photo by Imogen Cunningham, courtesy of the Imogen Cunningham Trust

Imogen had come at a crucial moment in Weston's affair with Mather. In Imogen's poignant images of them, their faces reveal the impending collapse of their relationship. Weston is looking off into the distance ready to move on, rather cold and indifferent. Margrethe is distressed and lost. These images are remarkable in capturing this painful and intimate moment in a way I don't remember ever seeing in another photographer's work.

It is a relationship seen photographically from an independent woman's point of view, and it is evident that no matter how much she disliked Weston's perfidy, Imogen was more disturbed by Mather's passivity.

A master's wisdom and restless eye

When I met her that time in Seattle, she walked with a cane but retained her sharp tongue and her memories. She told me: "Once, a woman who does street work said to me, 'I've never photographed anyone I haven't asked first.' I said to her, 'Suppose Cartier-Bresson asked the man who jumped the puddle to do it again -- it never would have been the same. Start stealing!"

Despite her age, she still had a restless eye. Taking her around Seattle's University District, she reminisced about how much it had changed since she was a student there. Yet while she spoke, she kept looking down at the Rolleiflex hanging around her neck. As we walked, she cradled it in one hand, gently turning the shutter speed dial with her fingers. Every now and then she'd stop, lean on her cane and look into the viewfinder to snap a picture. Occasionally, she'd look up at me and smile.

Is there any wonder why I -- and so many others -- loved her?

Self Portrait, 1974

Photo by Imogen Cunningham, courtesy of the Imogen Cunningham Trust

To see many more of Imogen's wonderful images, visit the Imogen Cunningham Trust archives. Below, you can watch an excerpt from Meg Partridge's Academy Award-nominated documentary, "Portrait of Imogen Cunningham."