An ocean of possibilities: Tips on shooting in and around water from adventure photographer Chris Burkard

From placid morning lakes to surfable ocean waves, water offers photographers a diverse and ever-changing subject. Its constantly shifting forms and interplay with light, temperature, and wind can make it one of the most fascinating and beautiful natural elements to shoot—and also one of the most challenging.

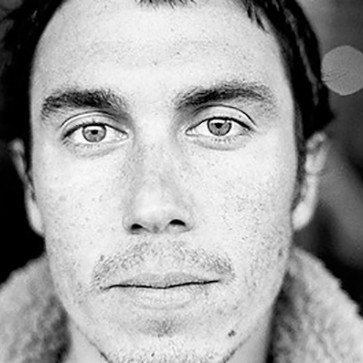

To learn about how to work with such a fluid subject, we talked with Chris Burkard, whose love of photographing the ocean and water sports propelled him into a career shooting for a wide range of top-tier commercial and editorial clients. His work has taken him around the globe to capture expansive natural vistas, adventure sports, and outdoor lifestyle scenes, and his affinity for bodies of water has often led him to include them in his striking imagery.

Burkard explained how he finds new perspectives on the natural world, talked about the tools and techniques he uses in and around water, and gave us some tips on how to stay safe, identify the optimal times and conditions for shooting in a given location, and incorporate human subjects into a scene.

Aimee Baldridge: How did you get into photographing in and around the water?

Chris Burkard: That was just a byproduct of me shooting surfing growing up and working on staff for surf magazines for a long time. I started getting in the water at probably about three or four, going with my mom to the local beach. I’ve always been drawn to that culture and had an understanding of it. A big part of that culture is shooting in the water. I think that was my first desire—I wanted to shoot in the water. That’s why I got a camera, the fact that I was psyched on getting in the water and shooting my friends and being a part of that.

Surfer near a volcano in the Aleutian Islands. Photographed with a Sony SLT-A99V and Sony FE 16-105mm f/3.5-5.6 lens at ISO 160 with an f/6.3 aperture and 1/640 second shutter speed. Photo © Chris Burkard.

AB: How do you prepare to shoot a body of water, given that it’s a subject that’s constantly changing?

Chris Burkard: I’m constantly looking at the light and how it’s evolving and changing throughout the day. I’ll study those elements and try to understand them the best I can so that I can make really good decisions as to what I should be doing. Simple apps can help to tell you about sunrise and sunset and things like that. SkySafari is a really good one. They tell you when the sun will rise and where, so that you can have a better idea of where the sun will be and where it’s going to set. That way I have a better working knowledge of where my light’s going to be and can plan my day a bit more accordingly. Because the light is really the biggest determining factor. Everything revolves around that one simple element.

Usually I think it’s best to try not to overcomplicate things. I learn the most about the ocean when I’m just sitting there watching it, when I take the time to slow down and give myself the opportunity to understand what it’s doing and how it’s reacting. If I want to shoot a place with the best light possible, I really want to give it the time it deserves to understand it. The best photographs that I get are of the places I’ve gone back to.

Secret beach lookout, Oregon. Photographed with a Sony a7 and Sony E 10-18mm f/4.0 ED OSS lens at ISO 50 with an f/8.0 aperture and 2 second shutter speed. Photo © Chris Burkard.

AB: When you keep going back to a particular place, how does the way you photograph it change?

Chris Burkard: I place a huge emphasis on being able to have personal experiences in places where you go. For me it’s never enough to go there and have a cookie-cutter experience on a tour bus. I want to go camp. I want to be deep inside the landscape. I want to spend time getting cold and feeling beat up when I’m shooting images. And I know that no photograph I shoot is ever going to be worth not coming back with a good experience, or a real, personal experience. I don’t want to come back from a trip and say, “Wow, I shot a ton of awesome images, but I can’t even remember a cool story to tell about what it was like because I was so inundated with having the camera in front of my face.”

Kayaking on Maligne Lake, Jasper National Park, Alberta Canada. Photographed with a Sony a7S and Sony FE 24-70mm f/4.0 ZA OSS Zeiss Vario-Tessar T* lens at ISO 250 with an f/4.0 aperture and 1/400 second shutter speed. Photo © Chris Burkard.

AB: You sound almost like a portrait photographer in the way you talk about developing a relationship between yourself and your subject.

Chris Burkard: I feel that’s so important, to have the desire and need to know your subjects intimately. And for me, it isn’t just true for the landscapes or people I’m shooting—it’s true for guys I’m traveling to Russia or Norway or Alaska to shoot with for two weeks. I want to make sure these are people I can trust, that they care about me and I care about them. For me it’s always kind of hard to be thrust into a random scenario with somebody you barely know.

Nature's recliner, Iceland. Photographed with a Sony a7 and Sony FE 24-70mm f/4.0 ZA OSS Zeiss Vario-Tessar T* lens at ISO 50 with an f/4.0 aperture and 1/200 second shutter speed. Photo © Chris Burkard.

AB: Speaking of being thrust into random scenarios, are there safety measures to take when photographing water that people don’t always think of?

Chris Burkard: If you’re going to shoot in cold water, it’s one thing to get out in the water and shoot, but it’s another to give yourself enough time and energy to get back safely to land. I’ve had times when I’ve almost gotten frostbite or I needed to get walked in or helped out, and it’s always been about me pushing a little too far. You need to evaluate the amount of energy you need for your whole journey. If you start to lose your feeling in your feet or hands—you have to use those to get home.

I never try jumping into any body of water if I don’t feel comfortable with it or have an exit plan or look 360 degrees around. I want to know what it’s doing and where I can get out if something bad happens. If I get stuck out to sea, what’s my plan? Make a plan before you go.

AB: Do you wear a drysuit in those cold water settings?

Chris Burkard: No, just a wetsuit. Because when you’re at the surface of the water and you need to go under the waves, you’re going to need to be flexible and move very quickly. It’s not like diving in cold water. You have to move around a lot, so it limits the amount of equipment you can bring.

AB: What are you shooting with these days?

Chris Burkard: My current kit is the Sony a7R II and an a6000, and I usually bring an a7S II also. And I bring a myriad of lenses: 24-70mm, 70-200mm, 16-35mm, and a fisheye adapter on the 28mm.

I’ve been using Sony products for four or five years. I had the NEX-5 and NEX-7 prior to the a7 line. I didn’t move to Sony because I was like, “Oh, the technology is better!” I moved to Sony because I needed a lightweight camera that I could shove in my jacket and still shoot really powerful APS-C images when I was traveling to Norway years ago. It was like: Sony’s the only one that makes this APS-C sensor and can still shoot 10 frames per second and do all this stuff. So that was the first thing that brought me to the camera.

And then I really loved the way it was operating and the way it felt. I loved the features—things like direct manual focus. So it made sense for me and I adopted the cameras really quickly. As the series became more advanced with the a7 and a7S, I just kept using them. It wasn’t a transition that I intended to have, because I was shooting Nikon and being sponsored and supported by Nikon too, so it was a shift for sure.

Iceberg surf lineup, Iceland. Photographed with a Sony NEX-7 and Sony E 18-200mm f/3.5-6.3 OSS lens at ISO 100 with an f/8.0 aperture and 1/800 second shutter speed. Photo © Chris Burkard.

AB: I assume you shoot with underwater housings often. What kind do you use?

Chris Burkard: There are a couple different ones. It all depends on the job. There’s an ewa-marine, which is just like a plastic bag. There’s also a Meikon housing for the a6000. I’m usually using those housings for the a6000 because I like the fact that the camera can shoot really fast frame rates.

Housings differ pretty dramatically if you’re going to dive with them, because dive housings actually seal underwater. They’re much different than, say, a surf housing that’s really meant to be used at the surface of the water.

For me there’s not really one perfect one. You use the housing that makes the most sense depending on where you are and what you’re doing. If you’re traveling super far and really lightweight and can’t bring a big housing and a lot of gear, then you might use a certain housing. If you’re going to be in a really intense scenario with big surf, then you would use a different housing. Most of my work is traveling pretty far, so I’m using really lightweight housings and trying to have the ultimate travel kit.

Kayaking in Westland National Park, New Zealand. Photographed with a Sony a6000 and Sony E 16-70mm f/4.0 Zeiss Vario-Tessar T* ZA OSS lens at ISO 500 with an f/4.0 aperture and 1/80 second shutter speed. Photo © Chris Burkard.

AB: I guess that’s another reason you like the small cameras?

Chris Burkard: Yes, completely. In the past I’ve been swimming around places with 12-pound and 15-pound housings, and that is not something that’s fun to move around with.

AB: Are there other tools you always carry when you’re photographing water?

Chris Burkard: I always try to bring a polarizer with me, just because if you’re shooting a really reflective surface, using a polarizer can cut the reflection and give you a little more saturation. I always bring a tripod just in case, although I prefer not to shoot with a tripod, simply because I love the freedom of being able to walk around and have flexibility. And I’ll bring a handful of filters, including a gradient filter, because sometimes you get a really bright sky and a dark body of water.

A crisp morning in Yosemite Valley, California. Photographed with a Sony a7 II and Sony E 10-18mm f/4.0 ED OSS lens at ISO 250 with an f/5.0 aperture and 1/640 second shutter speed. Photo © Chris Burkard.

AB: What about if you want to capture reflections on water?

Chris Burkard: Getting up really early when the water is still is super important. The earlier you get up the higher the chances are going to be that you’re going to find that.

AB: What do you need to know about the wind when you’re photographing water?

Chris Burkard: Usually you want the wind to be offshore. It cleans and grooms the water. What I mean by offshore is that it’s billowing away from the water’s edge toward the ocean. You’re not getting sea breeze and you’re not getting particulates in the air from the wind blowing toward you off the ocean. It’s clearing out the sky. It’s making things more clear and visible.

Mulafossur waterfall, Faroe Islands. Photographed with a Sony a7 and Sony E 10-18mm f/4.0 ED OSS lens at ISO 100 with an f/14.0 aperture and 5 second shutter speed. Photo © Chris Burkard.

AB: What do you think is a good way for landscape photographers to get started shooting the ocean and other bodies of water?

Chris Burkard: Finding an interesting background is going to be the first and most important thing you can do with your work—a background that your viewer can digest. I always try to find ones that are recognizable, like a mountain, that I feel people can really grasp. What that does is give your image scale. I also really enjoy having some foreground—some cool rocks or grass or sand.

I think the most important thing you can do is be there early or late. The time of day is everything. You’re always going to create a more interesting image if you’re shooting early in the morning, over shooting late in the afternoon. It’s like the main ingredient that will set your images apart or make your work unique. So that’s the best advice I can offer.

Action sports can add another element. It’s something I love to do, and obviously my work has a lot of that element in it. I love bringing people into the shot. I think when you do that, it’s always a matter of giving that person a place to go. So if you have someone walking toward the beach, you should always make it look and feel like they’re walking toward something, not just sort of aimlessly in the landscape, bewildered or lost. It’s really nice when you can give that person a context to where they’re going and what they’re doing—sort of a story. You’re shooting a picture that’s meant to tell a story, so you should try to make that story understandable.

Standing at the edge of Godafoss waterfall, Iceland. Photographed with a Sony a7 and Sony FE 24-70mm f/4.0 ZA OSS Zeiss Vario-Tessar T* lens at ISO 50 with an f/11 aperture and 3.2 second shutter speed. Photo © Chris Burkard.

AB: A lot of your images show people from the back, going into the scene.

Chris Burkard: That’s correct. They’re leading you somewhere. The subjects that I’m shooting, the people I’m shooting, are usually participants. I’m usually not just shooting people standing there. They’re actually going there or they’re part of the landscape. They’ve hiked up to that ridge line, or whatever it is. So it’s always important to make it feel like they’ve arrived or they’re going somewhere, or just add some movement. And that can be super subtle—the way their legs or their bodies are positioned.

Aerial view of the Grand Prismatic Spring, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming. Photographed with a Sony a7 II and Sony FE 70-200mm f/4.0 G OSS lens at ISO 100 with an f/5.6 aperture and 1/400 second shutter speed. Photo © Chris Burkard.

AB: You also have a lot of aerial shots. How do you find those perspectives?

Chris Burkard: Obviously flying, which is one of my favorite things to do. I put a lot of emphasis on that in my work—going out and flying and shooting things from different perspectives. Just going to a place like Iceland, for example, 10 or 20 times—it makes you want more. It makes you seek out another way of photographing it. I’m always looking for the next angle, and for me that’s what aerial photography was.

Aerial view of braided rivers in Iceland. Photographed with a Sony a7R II and Sony FE 24-70mm f/4.0 ZA OSS Zeiss Vario-Tessar T* lens at ISO 200 with an f/5.0 aperture and 1/500 second shutter speed. Photo © Chris Burkard.

AB: Do you use helicopters?

Chris Burkard: Usually planes because they’re cheaper to rent. I’m also looking at how to get licensed myself.

AB: What about drone photography?

Chris Burkard: I like shooting with them, but it’s not usually my forte. I’m usually wanting to get to places that are pretty remote and off the beaten path. Traveling into some of those places with drones is not the easiest thing. It’s a whole other bag you have to bring, and it’s a whole other process. It’s not a quick and easy thing. And then when you get there, it’s like: Do I shoot photos or do I fly? The light might only be good for so long.

They’re good to have when opportunity calls for it, but I find that most places people are flying with drones have been shot; they’ve been done. For me, aerial photography provides the opportunity to get to places you could never drive to. To fly a drone, you have to drive there first. So that’s the difference for me: A plane provides you access. It also gives you the ability to shoot different lens lengths and control your scenario. But they’re two different things. The drone is you shooting from 0 to 1500 feet off the ground and a plane is shooting 500 to a few thousand feet up. So we’re talking about totally different scenarios.

Float Plane transport, Washington State. Photographed with a Sony a7 and Sony E 10-18mm f/4.0 ED OSS lens at ISO 200 with an f/5.6 aperture and 1/100 second shutter speed. Photo © Chris Burkard.

AB: What lenses do you like for aerial shots?

Chris Burkard: I usually shoot a 16-35mm and a 24-70mm. Occasionally I’ll shoot a 70-200mm. You need the range. It’s not controlled. You might do a pass over one subject ten times and see different perspectives of it, so you need to zoom in and get it as much as you can. Prime lenses can be pretty limiting in a plane.

Shooting aerials over the ocean can be really incredible. Any water source you shoot over—that’s when it’s imperative to have a polarizer, because you’re usually looking straight down at the water and there’s a ton of reflection on it. It really helps to give you the maximum of vibrance and color out of the sea.

Aerial view of the Canadian Rockies. Photographed with a Sony a7S and Sony E 10-18mm f/4.0 ED OSS lens at ISO 320 with an f/4.0 aperture and 1/50 second shutter speed. Photo © Chris Burkard.

AB: Because otherwise you wouldn’t capture the texture of the surface?

Chris Burkard: Yeah, you can’t see it. If you look down on a river in the sunlight, you’re just going to see a glare, right? Having a polarizer can be the difference between actually seeing what you’re photographing and just having a big, blown-out blob of light there.

AB: You’ve photographed water from so many perspectives, and it’s such a diverse subject. Is there something about it that sets it apart from other kinds of subjects and keeps you coming back to it?

Chris Burkard: The ocean was my first passion. It’s always been interesting to me, because everywhere you go globally you see different sides of it. You’re never looking at the same wave twice. You never even see the same beach twice, because it’s constantly changing. So that has been something pretty cool to know and experience. It’s been pretty important in my work. I can still see different perspectives, different sides. You’re never really thinking you’ve seen it all.

The Matterhorn lit up by the Milky Way, Switzerland. Photographed with a Sony a7R II and Sony FE 28mm f/2.0 lens + Fisheye Converter at ISO 8000 with an f/3.5 aperture and 25 second shutter speed. Photo © Chris Burkard.

This interview was made possible by support from Sony's Artisans of Imagery program. For more about Chris Burkard, find him on Sony's Alpha Universe site or visit his website.

Want to read more interviews like this one? Check out our other Sony Artisans of Imagery interviews below:

Beat wedding-shoot anxiety: Wedding photography tips from world-class pro Scott Robert Lim

Chasing moonbows: Tips on working with extraordinary light from landscape photographer Don Smith

Fast, far, and wide: Tips for intrepid photographers from adventure sports shooter Gabe Rogel

Background first; the subject can wait: Unusual advice from Nat Geo pro Ira Block

No truth in photography? Photojournalist Ben Lowy on making (not taking) images