Mirrorless, Mirrorless on the Wall: Part I

posted Wednesday, August 22, 2012 at 3:52 PM EDT

Today’s post is one of those exercises in randomness that I just have to do every so often. I’ve been working with mirrorless cameras lately. That led to several people reminding me that two years ago I predicted mirrorless cameras would largely replace entry-level SLRs.

Today’s post is one of those exercises in randomness that I just have to do every so often. I’ve been working with mirrorless cameras lately. That led to several people reminding me that two years ago I predicted mirrorless cameras would largely replace entry-level SLRs.

After careful evaluation I have to admit I was only 62.5% correct. While mirrorless is the fastest growing segment of the non-cellphone camera market, it hasn’t replaced entry-level SLRs by any means. So I thought I’d look at why I was, uhm, less correct than I would like to have been (that’s male for wrong).

This post isn’t about who has the best mirrorless camera this quarter. Rather it’s about how the various companies have approached the mirrorless market, what the market seems to be looking like, and what I think will happen next. Since I was 62.5% correct two years ago, hopefully with more time for observation I’ll be 75% or so correct on what will happen next. Or maybe not. Most of the predictions will be in Part II of this series, though.

The Story of CaNikon and the Seven Dwarves in the Land Without Mirrors

Once upon a time there were two huge ogres named Canon and Nikon, who made almost all of the cameras that serious photographers used. The only other cameras were made by the Seven Dwarf Companies: Pany, Oly, Fuji, Sony, Penty . . . never mind. I just realized I was heading for Ricohy and Samsungy. We’ll drop the dwarf names quicker than I dropped Calculus III back in college.

Public domain image from 1937 Snow White trailer, courtesy Wikipedia.

Now in reality most of the Dwarves are far larger corporations than the two ogres, but their camera divisions aren’t. Truth be known, Nikon is the only company that makes the majority of their revenue from photographic equipment. Canon makes a very significant portion (not most) of their revenue in imaging, but that includes a very large video imaging division. The others are either electronics companies or medical imaging companies that also make cameras and lenses.

To put it in perspective, Samsung is by far the largest company involved in imaging with revenues of around $145 billion, followed by Panasonic ($99 billion), Sony ($82 billion), Canon ($44.5 billion), Fujifilm ($28 billion), and Ricoh ($24 billion)(1). Nikon’s revenue, for perspective, was $11.6 billion(2), which was a bit more than Olympus.

For a little more perspective, Ricoh bought the entire Pentax camera company for $124 million, lock, stock, and patents. That’s about 1/3 the price of a small-market NBA team. Personally, I’d much rather have three camera companies than a small market NBA team. The camera companies at least might show a profit.

I think this perspective is important. Except for Nikon and Canon, none of these companies would roll over if their camera division disappeared tomorrow. It’s not the focus of their business. Photographic equipment accounts for less than 20% of revenue; often a lot less than 20%.

This can be a disadvantage, of course. The camera division gets whatever resources the company’s directors decide to send their way, and the camera division isn’t likely to have as much clout as several of the other divisions in the annual budget meetings.

On the other hand, some of these companies may decide to let the little camera division swing for the fences and be as innovative as they like. It’s not like they’re making a bucket of money anyway. A ‘go big or go home’ philosophy may be an exaggeration for even the most aggressive of them, but logic would suggest a well-healed company with a small camera division would be willing to take some risk. A company depending on the camera division’s revenues to keep the entire company afloat might want to protect the status quo a bit.

So Once Upon a Time...

Innovative smaller companies being innovative started this mirrorless thing. The Seven Dwarves were making some nice cameras, but weren’t making huge inroads in SLR market share. Sony made a splash with the Alpha cameras, but then seemed to get distracted, as Sony often seems to do. Then some of the smaller companies decided to shake things up a bit. Instead of the same-old-same-old, they were going to start a game of TEGWAR--The Exciting Game Without Any Rules--and change things up.

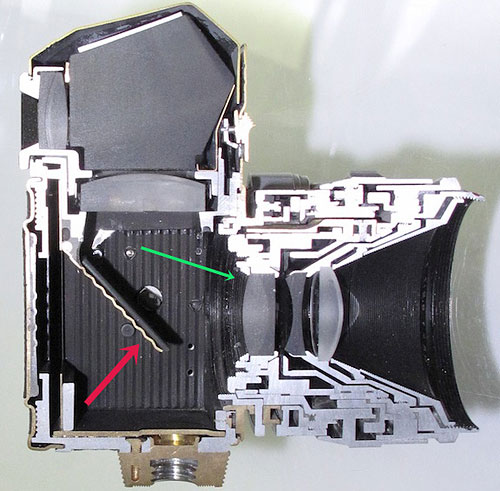

The idea was simply brilliant: just remove the phase detection autofocus system and the optical viewfinder. Do that and you can remove the entire mirror assembly. Now the backfocus distance (the distance from the back of the lens to the sensor) can be much shorter since you don’t have a swinging mirror to clear. You lose a couple of things (phase detection autofocus and the optical viewfinder) but you can use contrast detection autofocus and add an electrical viewfinder (EVF) or (ugh!) try to get by with the LCD.

All that stuff you eliminated was bulky and expensive, so cameras could become much smaller and less expensive. (Well, in theory they could become less expensive.) There weren’t a lot of lenses, but since the backfocus distance was short you could add an adapter to use legacy lenses for a while. It probably was the most brilliant idea since the Exacta introduced the world to SLR cameras back in the 1930s.

When I handled my first mirrorless, interchangeable lens camera, back in 2008, I was certain this would change everything. It was smaller. It would be less expensive. It needed a little more development and some lenses, but that would be just a matter of a couple of years. The lack of phase detection meant slower autofocus, but not that many people use entry level SLRs for action photography. Electronic viewfinders were getting good. How could it miss?

What has held back mirrorless?

A lot of you are going to get worked up about the ‘held back’ comment. After all, mirrorless is the fastest growing segment of the camera market. But remember, two years ago I said mirrorless would largely replace entry-level SLRs and that certainly hasn’t happened. So maybe “held back from fulfilling Roger’s optimistic prediction” would be more appropriate.

My prediction was off for a couple of reasons. It’s not because entry-level SLRs are so much better or less expensive than they were 3 years ago. Let’s see if I can break down what did happen.

Economic Factors

With all due respect to the Epson RD-1 and Leica M8, mirrorless cameras really began releasing in late 2008 and throughout 2009. This means they were being developed just before the Great Recession started, and released in the depths of it. I can only speculate, but it seems reasonable that some manufacturers scaled back research and development during this time. Certainly a couple of companies found themselves in some financial distress. It may not have been a big factor, and nobody outside the companies knows exactly how much of a part it played, but it would be reasonable to think it had some effect in slowing development.

Sony's stock price from 2008 to 2009, courtesy of Wikinvest.

There was also the pricing factor, which was my first error back in 2009. If you’ve looked inside a regular SLR and a mirrorless camera, you cannot possibly doubt the mirrorless is far less expensive to produce. I made the assumption that the mirrorless cameras would be priced lower than the entry-level SLRs way before now.

Unfortunately, that didn’t happen. Current generation mirrorless bodies run from $1799 down to $470. Prosumer and Consumer SLRs from $1700 (Nikon D300s) to $480. So the price differential between mirrorless and prosumer / consumer level SLRs didn’t really happen.

It probably would have been obvious if I had thought it through. Nikon and Canon have had entry-level SLRs at just under the $500 price point since around 2006, so they haven’t changed anything. I suspect those are break-even or loss leader price points. The mirrorless companies have to make a profit when they sell the camera, because they aren’t trying to lure entry-level photographers who will eventually climb up their equipment food chain.

Lack of Lenses

I was wrong here, too. I knew lenses would take a while, but didn’t realize it would be this long. For serious photographers, this has to be the biggest factor that prevented the adoption of mirrorless cameras. It has affected some companies (cough, Sony, cough) more than others, but lack of lenses has certainly held back mirrorless as much as any other factor.

It has become very obvious that several of the Seven Dwarves are really electronics companies. Camera companies make optics. Electronics companies make a camera body and get Leica or Zeiss to design a generic zoom lens to slap in front of it. That formula worked fine for fixed-lens point and shoots, but more serious photographers generally want lens options.

The real camera companies all tried, at least. I assume Olympus just didn’t have the resources to redesign their lenses for the shorter backfocus distance of mirrorless systems quickly, but they certainly are turning some superb ones out now. Nikon did release a reasonable set of lenses with the J1/V1 cameras. Fuji had several lenses ready with the X-Pro 1 release and a very clear timeline for more. Pentax designed their mirrorless (rightly or wrongly) to use their entire existing lens lineup, which means it had the largest native-mount lens selection of any mirrorless the day it was released.

Canon, surprisingly, may become the exception to that rule. They have only announced two lenses releasing with the EOS-M. They have, however, released several small lenses (40mm pancake and 24 and 28mm IS f/2.8) for SLRs. Perhaps we’ll see those ported over to EOS-M mount rather quickly. Or maybe not.

The ‘mostly electronic’ companies were a bit more varied. Panasonic might not have great in-house lens design abilities, but they did let Leica design a couple of superb prime lenses for their mirrorless systems. Samsung has nine lenses available for their NX cameras, an excellent showing. (Although someone needs to tell their marketing department; the lenses are buried three deep under the camera page in the ‘accessories’ section.) Sony proceeded to make a series of breathtakingly small, feature-rich, excellent mirrorless cameras. But if you want to shoot native E mount lenses, well, much of that excellence is lost.

Diffraction Limits

Do any of you remember that Olympus announced, back in 2009, that the Four Thirds group would not increase resolution past twelve megapixels? They changed their mind, obviously, but they didn’t change their lens designs. If you look at Micro Four Thirds zoom lenses, they have had a strong tendency to be aperture-impaired. Most zooms are f/5.6 or even f/6.3 at the long end. That’s not great on any camera, but it’s especially bad when you put them in front of sixteen megapixel Four Thirds-sized sensors that become diffraction limited at f/8 or perhaps even f/5.6.

I realize that a small megazoom lens helps the ‘purseability’ of the mirrorless cameras; it’s attractive to the point-and-shoot-move-up customer. But it drives a lot of people right past mirrorless to the intro-level SLR that can mount an f/2.8 zoom or f/1.4 prime lens, or that isn’t diffraction limited with an f/5.6 lens.

They thought we would like huge lenses on adapters

It also seems apparent that several companies thought we would be happy putting a big adapter and an even larger lens on these tiny cameras. I hear it a lot from various fanboys when I trash a lens lineup (see Sony above); “You can shoot the wonderful Gazooma Lens on an adapter.” OK, so I buy this 14 ounce camera that I can take anywhere, and you suggest the best lens for it is 8 inches long, weighs two pounds, and I can go have a coffee while I wait for it to autofocus. If I’m taking the big-boy lens, then I might as well take the big-boy camera.

Image courtesy of Roger Cicala / LensRentals.

By their nature, adapters are problematic. Then there are the possibly accidental (yeah, I’m just as suspicious as everyone else) branded adapter incompatibility issues, particularly in the Micro Four Thirds world. Even when they work properly, any adapter adds two more lens-camera interfaces so that you never can be quite sure when you’ll start getting side-to-side or top-to-bottom tilt. Not to mention slow (or nonexistent) autofocus with high current drains. And, of course, some of the adapters are about as big as the cameras. I understood this as a stopgap measure. I just didn’t realize that they'd be stopping the gap for three years.

Short Backfocus Distance

I realized the mirrorless cameras all had this, of course. (For those who don’t know the term, it basically means the back of the lens is much closer to the sensor.) I didn’t consider that short backfocus distance would change the angle of light rays impacting on the sensor, and that the sensor’s microlenses might not like this. I suspect this has something to do with why the lenses have taken longer to develop than I expected. It certainly has a lot to do with why some lenses on adapters behave differently on mirrorless cameras. Wide-angle Leica-mount lenses on NEX bodies are the best documented example, but there are certainly others that are more subtle.

“They aren’t the Same” Resistance

This one is something I never once considered; I thought it was self-evident. I wanted a small camera that I could carry anywhere conveniently that would take excellent pictures. A lot of people wanted a small camera they could take anywhere that would take exactly the same image as their SLR did. That isn’t happening.

The depth-of-field is different (I refuse to discuss how it’s different: that leads to 76-post long forum discussions about how it can be the same if you use a different focal length, aperture, shooting distance and sacrifice a chicken at midnight. But in general it’s different.) The native resolution is different. The aspect ratio may be different. ISO performance may be different.

The bottom line is it’s a slightly different tool. I’ve learned that ‘different’ can be an advantage in some situations and a disadvantage in others. Medium format is different, too, with advantages and disadvantages. I don’t think this really affected my initial predictions about mirrorless, though. I didn’t expect many SLR shooters would give up their full-frame camera and move to Micro Four Thirds, for example. I thought they would use a mirrorless as a go-anywhere camera to compliment their SLR. But at least a few people have gone mirrorless full-time and dropped their SLRs.

So, Will I Eventually be More Correct than I Recently Was?

Yes, absolutely. More or less. I still think mirrorless takes over most of the better-than-cell-phone market from entry-level SLRs. The speed and servo functions of phase-detection AF will still pull parents of young athletes, birders, and others who need that advantage toward an SLR, so that segment will never die out entirely, of course. But for the many people, every year, who decide they just want better photographs than their cell-phone or point-and-shoot, I see mirrorless as the logical next move.

There are also old photographers like me--I mean, like I will be some day--who want a small, convenient camera with excellent image quality they can carry everywhere. I’ve always owned a top-end point and shoot, but now I’ve dropped that for a mirrorless system. It’s my go everywhere camera now, although I still reach for an SLR and specific lenses for a specific purpose. But for the price of a new 70-200mm f/2.8 I have an excellent, fairly complete small camera system that stays with me all the time.

I think the fun speculation, though, is what’s going to happen within the mirrorless segment, not what happens overall. That will come in part two!

(Roger Cicala is the founder of LensRentals.com. Visit LensRentals.com to check out that cool lens you've been hankering for, and for some of the best customer service on the Internet!)