The birth of travel photography: Du Camp and Flaubert’s 1849 trip to Egypt, North Africa and the Middle East

posted Tuesday, October 30, 2012 at 4:25 PM EDT

One of my favorite photography stories is about one of the world’s first travel shoots. It's a little-known, true-life adventure that puts Indiana Jones to shame. I discovered the tale years ago at a flea market when I bought an old, yellowed paperback titled "Flaubert in Egypt."

The book is composed of excerpts from the journals of two young Frenchmen, Gustave Flaubert -- who had yet to write the literary classic "Madame Bovary" -- and his rich Parisian friend Maxime Du Camp. Flaubert, in 1849, had dropped out of college and was at loose ends. Du Camp suggested that they go and photograph the monuments of the "Orient." Flaubert jumped at the opportunity, and that autumn the two hopped aboard a ship bound for Alexandria, Egypt.

Gustave Flaubert

Maxime Du Camp

Travel as we know it did not exist in the early 19th century. Only the very rich, mostly aristocrats, could afford the time or money for a "Grand Tour" of Europe -- a trip that by our standards was hardly grand. Most people had no idea of what the world looked like because, before photography, travel books featured only line drawings at best.

Capturing images by Calotype

Du Camp had studied photography, and for the trip took along his wooden Calotype camera, a tripod and jugs of chemicals. Invented by Henry Fox Talbot, Calotype photography was never very popular because Talbot strictly licensed his patented process. The fees he charged made it less attractive than the free public domain Daguerre process. But Du Camp smartly realized the advantage of the Calotype for travel. His camera was relatively small and easy to carry around. It used ordinary, readily available, high-quality writing paper as the media for its negatives.

Calotype camera

The writing paper itself could be partially sensitized in a hotel room or even a tent, and once dried, be conveniently stored and carried around until needed. The big drawback was that while the Daguerreotype is incredibly detailed, a Calotype print is much softer because the print is made from a paper negative. However, by shooting paper negatives, Du Camp could make any number of contact prints from them upon his return to Paris. By comparison, the Daguerreotype was a singular photograph -- an image on a metal plate -- from which no copies could be made. Du Camp was planning ahead to produce multiple copies of his travel albums.

What they saw

Du Camp and Flaubert traveled through North Africa, Egypt and the Middle East, taking photos and keeping detailed, although often contradictory, diaries. It was a landscape as dangerous and chaotic as it is today. They had to fight off bandits and the occasional anti-government rebels who fought from camelback. They got arrested as spies, which they may very well have been, and they sailed down the Nile on a “cange” or small boat, with a crew that would have frightened even Jack Sparrow.

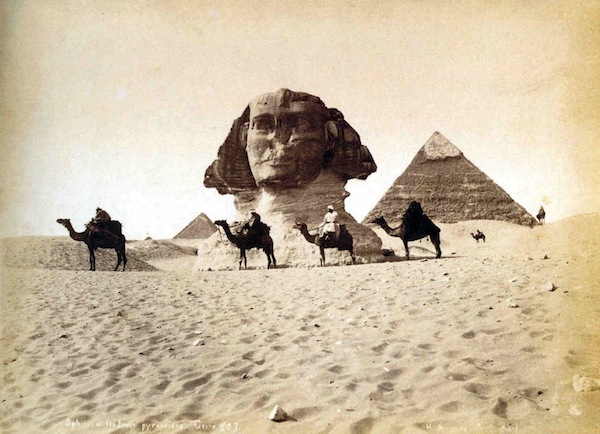

Naturally enough, their exploits also involved dangerous liaisons with native women, belly dancers and prostitutes, and the consumption of quantities of alcohol and exotic drugs. Despite these distractions, the men stayed focused on their mission, producing hundreds of photographs that captured, for the first time, some of the great manmade wonders of the ancient world such as the pyramids, the statues at Aswan, the Sphinx and more.

In his journal, Flaubert wrote of the Sphinx, “No drawings that I have seen convey a proper idea of it -- best is an excellent photograph that Max has taken.” Meanwhile, Du Camp wrote, “I am pale, my legs trembling. I cannot remember ever being moved so deeply.”

Photograph by Maxime Du Camp, 1849

How the photos were made

Arriving at a site, the work of making photographs would begin. Flaubert apparently would do his best to avoid actual work, letting the porters put up the darkroom tent, while Du Camp would scout out locations. After placing the camera on a wooden tripod, Du Camp would duck under a black drape so he could frame and focus his image on the groundglass.

Then he would go into his mostly light-tight darkroom tent and brush the sensitized side of the writing paper with a solution of gallo nitrate of silver -- a mixture of silver nitrate, acetic acid and gallic acid. This was an accelerator that increased the paper’s sensitivity to light. After blotting the paper dry and placing it in a light tight holder, he would go back and load it into his camera.

Now came the trickiest part of 19th century photography. It has always amazed me that these photographers worked without exposure meters. Exposure was learned strictly by trial and error. I often wonder if I could do that. (Later on, things got a little easier when photography guides shared recommended exposure times for most locations, latitudes, days of the year and weather.)

Once he found the right exposure time, Du Camp would remove the holder’s light slide and take the lens cap off. Using his pocket watch, he would time the exposure and then replace the cap. Exposure complete, he would return to the darkroom tent to develop the negative. This required brushing the paper with gallo nitrate again while gently warming it over a hot pot. This produced a visible silver image that was fixed with hypo, the same hyposulphite of soda modern film development uses. This dissolved the unexposed silver iodide, which was then washed away, leaving a pure silver image on the paper.

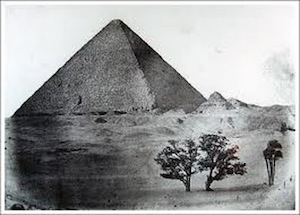

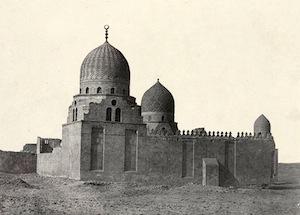

The Great Pyramid of Giza (left) and the Tomb of the Mamlouk Sultan (right)

Photographs by Maxime Du Camp, 1849

A photographic sensation

Upon their return to France, Du Camp made salted paper prints from his negatives. These were simply more Calotype papers, printed in contact with the paper negatives, to produce positive prints. The prints were mounted on heavy paper, and then bound in albums that Du Camp sold in 1852 under the title “Egypte, Nubie, Palestine, Syrie.”

This was arguably the world’s first travel photography book and the images amazed the public. It made Du Camp famous almost overnight.

Whenever I see a horde of tourists, cameras in hand, photographing everything in sight, I think of Gustave and Max. Today's snapshooters have no idea how hard it once was to photograph the world, something they can do now so easily with just the press of a button.

Ruins of Nubia

Photograph by Maxime Du Camp, 1849