William Eggleston: The world’s greatest photographer? Or the worst?

posted Thursday, April 25, 2013 at 4:56 PM EDT

Earlier this month, 73-year-old American photographer William Eggleston traveled to England to receive a Sony World Photography Award and to celebrate the opening of a permanent exhibition of his photographs at the Tate Modern in London. In reporting these two events, art critic Michael Glover of the Independent (UK) titled his article a little breathlessly, "Genius in colour: Why William Eggleston is the world's greatest photographer."

This may come as a shock to many photographers. I am even willing to bet that most people -- including many IR readers -- have never heard of William Eggleston before, much less have realized he was in the running for "world's greatest photographer."

Glover goes a little overboard with his praise when he writes:

"The way we do photography now would not have been the same without Eggleston. Martin Parr, Nan Goldin and Jeff Wall would not have been granted the permission to be themselves without Eggleston's example. It was he and not, say, Cartier-Bresson, who was the true revolutionary, which means that he has caused a lot of trouble in his time merely by being, quite unflinchingly, who he has been."

To be fair, Glover reminds readers that when Eggleston's work was first shown in May 1976 at New York City's Museum of Modern Art (MoMa), the New York Times called it "the most hated show of the year." Reviews were generally awful, with reviewer Hilton Kramer going so far as to say that the photos were perfect, "perfectly bad, perhaps… perfectly boring, certainly."

But what is it about Eggleston's photos that generate such praise and such vitriolic condemnation? And who is he anyway?

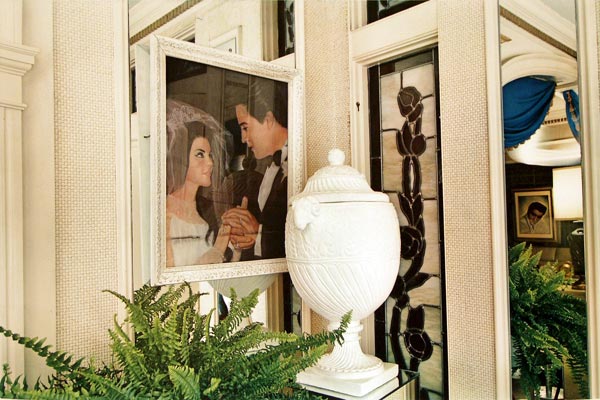

Untitled, William Eggleston © Eggleston Artist Trust. All rights reserved.

A portrait of the artist as a young man

William Eggleston was born in 1939 in Memphis, Tennessee to a family of well-to-do plantation owners, and grew up in Sumner, Mississippi. Most of his photos have been taken in the South, where he splits his time between his wife and family in one house and his mistress in another.

The young Bill was pampered by his grandparents and grew up without any direction in his life. He spent six years studying at various art schools, but never got a degree. Then in 1957 he got his first camera -- a Canon rangefinder -- which he'd soon trade in for a Leica. And then his world began to change.

Eggleston at first was inspired by the work of photographer Robert Frank, and the images in his book, "The Americans," as well as Henri Cartier-Bresson's "The Decisive Moment" and Walker Evans' "American Photographs." Cartier-Bresson had originally trained as an artist, too, and Eggleston recognized that his subtle use of geometry and composition echoed the Impressionist paintings of Edgar Degas.

"Photograph the ugly stuff"

But Eggleston had a problem. While Cartier-Bresson and others roamed the world photographing faraway places and important things, Eggleston was stuck in Memphis. His wife, Rosa, related that one day he told a friend that there was nothing to photograph because everything in the city was ugly. The friend told him to "photograph the ugly stuff."

Untitled, William Eggleston © Eggleston Artist Trust. All rights reserved.

Eggleston began to do just that and shot black-and-white images that echoed Frank and Cartier-Bresson. However, even in his early images, he was mapping out a new territory that other photographers had overlooked -- the world of the mundane and ordinary.

In 1967, he took his Leica and began to focus on photographing the banal, although now in color. Soon he had taken thousands of color images that he had printed at a local lab. He then met John Szarkowski, then head of the MoMa photography department and showed him what Szarkowski would later recall was a suitcase full of "drugstore" prints. But he felt strongly enough about the young photographer's images that he got the Museum to buy one of them.

Untitled, William Eggleston © Eggleston Artist Trust. All rights reserved.

Then in the early 1970s, Eggleston discovered dye-transfer printing on a trip to Chicago. He was in a large photo lab and saw their price list for prints. The dye-transfers were the most expensive but they were described as the ultimate color print. Eggleston later said of the experience:

"I went straight up there to look, and everything I saw was commercial work, like pictures of cigarette packs or perfume bottles, but the color saturation and the quality of the ink was overwhelming. I couldn't wait to see what a plain Eggleston picture would look like with the same process. Every photograph I subsequently printed with the process seemed fantastic and each one seemed better than the previous one."

In 1974, Eggleston put together a portfolio of images entitled "14 Pictures" and published a book of images under the title, "Los Alamos." He began to be noticed by the art and photography world, and in 1976, Szarkowski offered the young unknown his first show at Museum and called Eggleston the first "Modern" photographer.

Untitled, William Eggleston © Eggleston Artist Trust. All rights reserved.

Photographing democratically

I remember my first reaction to seeing Eggleston's images: It was astonishment. Here were gorgeous color photographs of nothing in particular, of seemingly random everyday objects and moments. It was totally unlike the art photography of the day, which had to be in black-and-white and was centered on photographers such as Ansel Adams and Edward Weston.

However, while critics like Hilton Kramer were put off by these images, many of us younger photographers viewed them with wonder. Rather than trying to explain the world as Adams and others did, here was a photographer who was simply showing it and letting the viewer imagine a narrative for the image.

Untitled, William Eggleston © Eggleston Artist Trust. All rights reserved.

Eggleston says that he photographs democratically -- all subjects are of equal importance (or of equal unimportance). At first this indifference is disturbing. It feels at times that his subjects are things Eggleston noticed out of the corner of his eye and the scenes are nothing particularly special or notable. And that's exactly what they are, and what he intended them to be. In his work there is none of the certainty of photojournalism, and certainly none of its social or political comment. As art critic Glover rightly says, 40 years ago Eggleston's big color prints were, "dismissed as banal, inconsequential and ramshackle in the extreme."

How else could you describe a luscious dye transfer image of the inside of a refrigerator, or explain Eggleston's most famous image, a bare light bulb in a fixture with white extension cords extending across a red ceiling?

Untitled, William Eggleston © Eggleston Artist Trust. All rights reserved.

Taking color to a new level

Eggleston's work not only challenged traditional photography, his use of color -- what he calls "ordinary color" -- took color photography to a new level. His images are postcards from the edge of the ordinary world, and it is his skill that turns them into something at once recognizable, yet often dark and ominous. These images of the "ugly things" do not try to make things ugly -- or for that matter make them beautiful. Eggleston's artistic vision doesn't allow that. He photographs simply what things are.

He was ahead of his time, too, in a way, and the world has finally caught up with him. His banal, "democratic" photographs are the forerunners of the millions of photographs taken every day with iPhones and tablets and uploaded to the Internet.

While there is no need to call William Eggleston, a "genius in colour" or the "world's greatest photographer," it is enough to say that he is truly a groundbreaking artist -- and, at age 73, one of America's national treasures.

Coinciding with Eggleston's visit to London to receive the Sony Award, it's nice to revisit the wonderful documentary the BBC has produced about him for its "Imagine" TV series. Called "The Colourful Mr. Eggleston," the video (which you can view in its entirety below) brings to life this amazing photographer and his art. For more information about his life, work and vision, and to see a wide selection of images, visit the Eggleston Artistic Trust.