‘If I could tell the story in words, I wouldn’t need to lug around a camera’: Celebrating social documentary photographer Lewis Hine

posted Friday, November 1, 2013 at 12:29 PM EDT

Photographer Lewis Hine changed the world with his camera -- and we are all the better for it. Professorial and bespectacled, he was a slight man who carried a big camera, and with his photographs was instrumental in ending child labor in America.

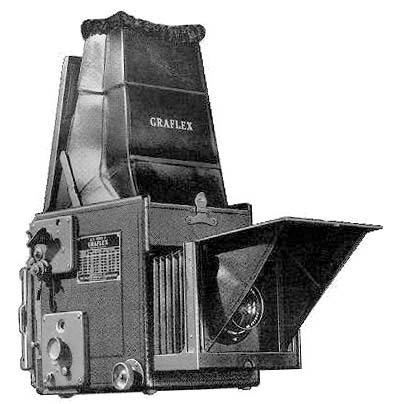

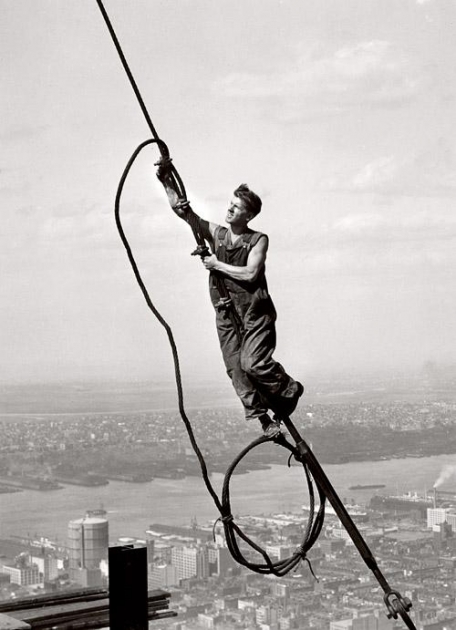

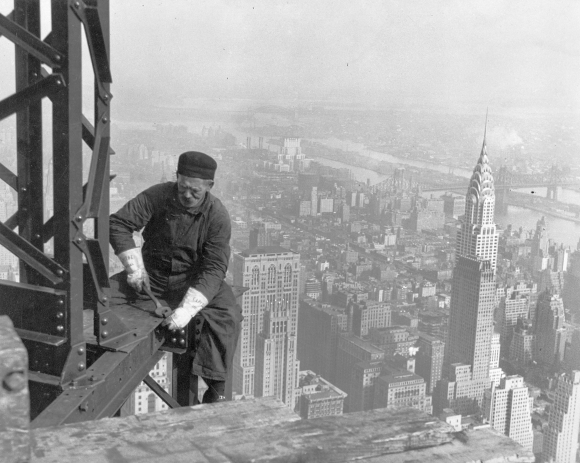

Though he is best known for those social documentary images, his work spanned far more than that. He was a superb photographer, a master of the Graflex camera, and his industrial imagery for example, was so elegant and powerful that he was hired in 1930 to document the construction of the Empire State Building.

"There were two things I wanted to do. I wanted to show the things that had to be corrected. I wanted to show the things that had to be appreciated." -- Lewis Hine

A rough, but determined start. Born in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, in 1874, his father died in an accident when Lewis was very young. Determined to go to college, he began working at an upholstery factory at the age of 15. But times were hard and when he lost that position he took on a series of small jobs, including selling door to door, working as a delivery boy and a bank janitor.

Finally, in 1900 he was able to enroll at the University of Chicago, and he studied the newly created field of sociology under Thorsten Veblen. He followed this with classes in New York City at Columbia University and NYU. But it wasn't until he was past the age of 30, and working as a teacher, that he seriously took up photography. He saw the camera at first as a tool for recording the social conditions he was researching.

"The dictum, then, of the social worker is 'Let there be light' and in this campaign for light we have for our advance agent the light writer -- the photograph." -- Lewis Hine

Perfect timing. His entry into photography came at a fortuitous moment. Since the invention of photography in 1839, photographers had viewed their images upside down on a groundglass. This made composition and focusing difficult. Worse yet, when the glass plate or film holder was inserted in the camera, the photographer lost the image entirely and was literally shooting blind.

Then in the 1890s, William Folmer invented a focal-plane shutter that could be placed behind the lens, just in front of the holder. Then he placed a mirror between the lens and the film. The mirror reflected the image onto a groundglass on top of the camera box, and photography was revolutionized. Finally photographers had a right-side up image to work with, making it possible both to focus selectively and to compose the image to the edge of the frame. Also, for the first time photographers could watch the action in the groundglass frame and select the "decisive moment" to snap the photo.

Hine used the Graflex and became a master photographer. Looking at his images today, besides their social value they were some of the earliest examples of what we recognize as modern photography.

"In the early days of my child labor activities I was an investigator with a camera attachment... but the emphasis became reversed until the camera stole the whole show." -- Lewis Hine

First foray into photography. Hine's first photographic job was working as a staff photographer for the Russell Sage Foundation in 1906, documenting the steel-making districts of Pittsburgh. In 1908, he was hired as the photographer for the National Child Labor Committee and with that left his teaching work.

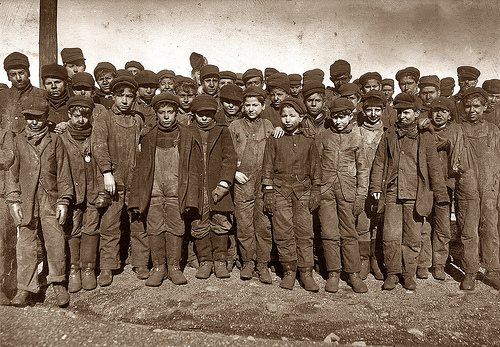

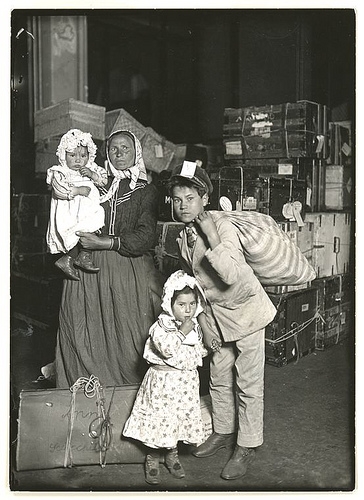

His assignment for the NCLC was to photograph children at work as part of the Committee's lobbying efforts to end child labor. Hine traveled across the Northeast and South, recording the plight of very young children at work in places such as cotton mills and mines.

He worked on this project for nearly a decade and said of it, "Perhaps you are weary of child labor pictures. Well, so are the rest of us, but we propose to make you and the whole country so sick and tired of the whole business that when the time for action comes, child-labor pictures will be records of the past."

With the onset of World War I, Hine worked with the American Red Cross recording their relief efforts in Europe. After the war he continued on a personal project photographing the human side of modern industry.

Creating an emotional connection. In all of his photography, Hine was aware that his images had to reach people emotionally rather than as polemic. A simple protest against child labor has no impact unless people empathized with his subjects. This is the key to the power of Hine's images.

In his images of children for example, we can feel his love for the kids. He doesn't pity them, he respects them, and the hard labor they do. He poses them looking directly into the camera, face to face with the viewer.

His industrial images on the other hand, are a celebration of the nerve and muscle of his subjects who tenaciously work with huge industrial machines. Charlie Chaplin in his movie "Modern Times" pays homage to one of Hine's iconic Pittsburgh images.

"I have had all along…a conviction that my demonstration of the value of the photographic appeal can find its real fruition bet if it helps the workers to realize that they themselves can use it as a lever even though it may not be the mainspring of the works." -- Lewis Hines

A life's work of documenting social conditions. Throughout the 1920s Hine's took on photo assignments with social service agencies such as the Amalgamated Clothing Workers and the Boy and Girl Scouts of America, as well as with industrial clients like Western Electric.

When the Depression stuck, Hine applied to Roy Stryker to work as one of Farm Security Administration photographers. But Stryker would not hire Hine because the photographer refused to sell the rights to the photographs to the FSA. Instead, Hine continued to document the efforts of the Red Cross in America's drought-stricken South, worked for the Tennessee Valley Authority and was the chief photographer for the Works Progress Administration's National Research Project. Around this time, too, his work began to get published in magazines like Life and Look magazines.

In 1930, Hine was hired to document the construction of the Empire State Building. Construction was extraordinarily dangerous in those days and few workers had any sort of safety gear. High in the air, most workers were untethered as they built the iron and steel frameworks in the sky. Hine shared their danger and took the same risks they did to get the best photos possible. Often, to get the right angle, he would be swung out beyond the building's frame in a specially designed basket suspended 1,000 feet above Fifth Avenue.

Recognition comes late in life. However, for all of the thousands of images he made, it wasn't until 1938 that the photography establishment took notice of him. That year he visited Beaumont Newhall, then curator of photographs at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City and showed him his portfolio. Newhall was impressed, and wrote an article about the photographer. In 1939, Hine earned his first "retrospective" show. Sponsored in part by photographers Alfred Stieglitz and Paul Strand, the show was a success and went on to several other venues.

But in a year that should have been his finest moment, Hine lost his wife, and through financial difficulties, also his home in Hastings-on-the-Hudson. He eventually had to apply for welfare and live in a small room alone. On Nov. 3, 1940, he died at the Dobbs Ferry Hospital from complications following an operation.

Throughout his life, Lewis Hine believed in the social importance of photography and he would say of it that it would, "Ever be the human document to keep the present and future in touch with the past."