The piercing eye of Brassaï: the stunning work of a master French photographer

posted Tuesday, January 7, 2014 at 1:34 PM EDT

"My ambition has always been to show the everyday city as if we were discovering it for the first time."

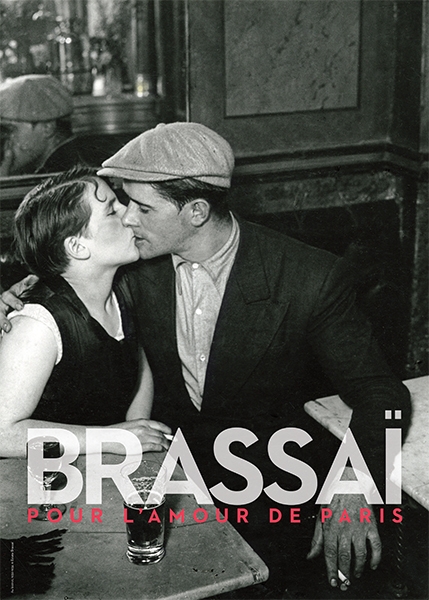

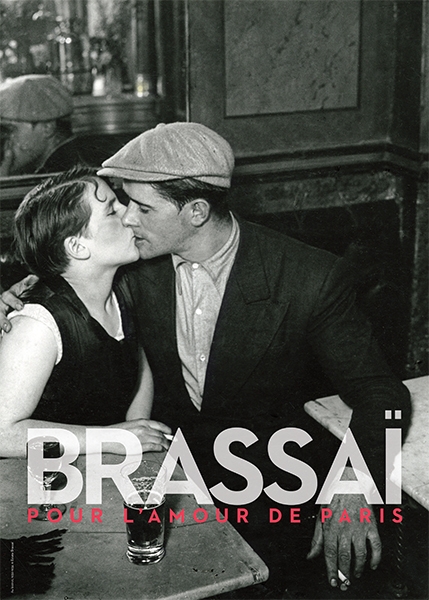

A superb new exhibition of photographs, Brassaï, Pour l’amour de Paris is on display at the Paris Mayor’s Office, the Hôtel de Ville. It is a reminder to all of us of the photographer who -- along with Henri Cartier-Bresson -- dominated European photography in the 1930s.

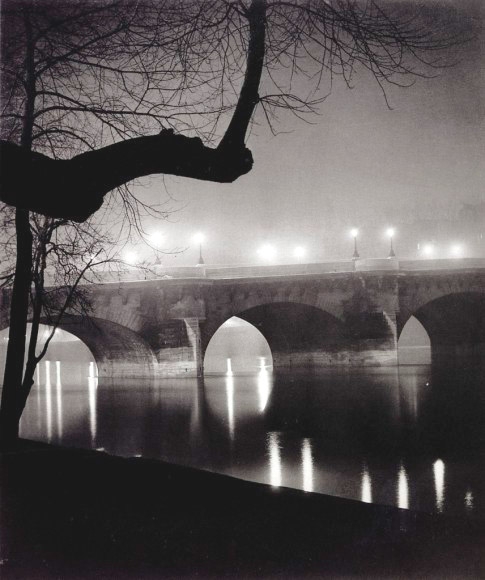

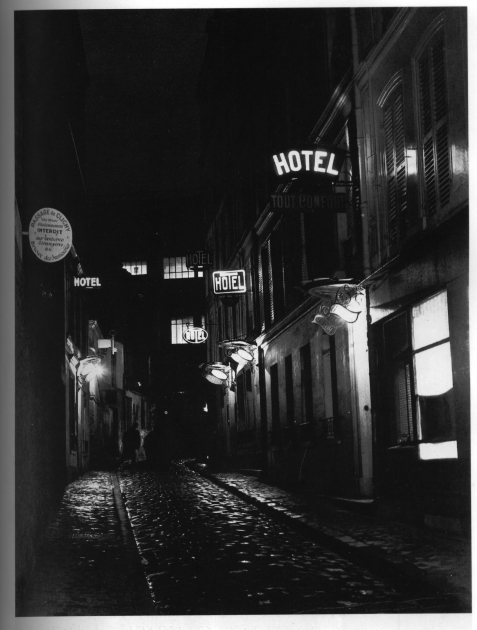

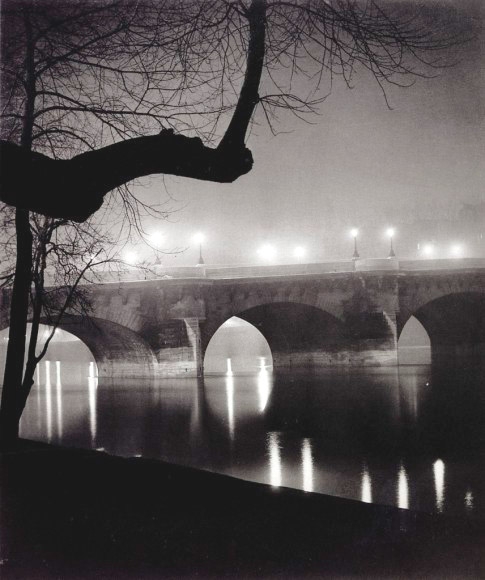

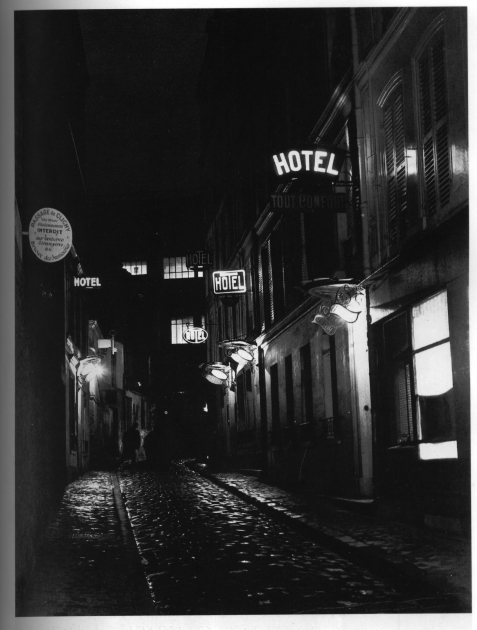

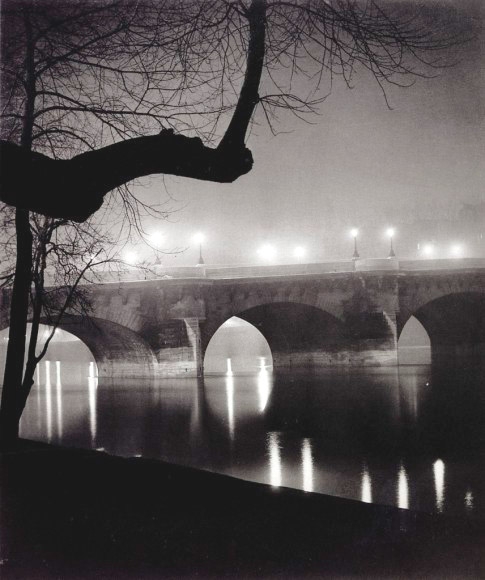

Brassaï became interested in photography as a way to record encounters on his nightly walks through the streets of Paris. He enjoyed these long strolls after dark and began carrying a camera and tripod in 1929. Two years later, he compiled some of these photographs in a book entitled Paris de nuit (Paris by night). It was a stunning collection of black and white images that juxtaposed luminous, dreamlike nightscapes with contemporary documentary images of the nighttime’s denizens. It was a technical marvel as well, for he was one of the first photographers to shoot extensively at night.

"Night does not show things, it suggests them. It disturbs and surprises us with its strangeness."

These photographs are very different from Cartier-Bresson’s as they are theatrical performances rather than decisive moments. Brassaï’s subjects are not only aware of the photographer, they collaborate with him. Brassaï’s unique style gave Paris de nuit its distinctive intimacy and led to its huge public success. It was a revelation too for his artist friends. Fellow night owl Henry Miller wrote:

"Brassaï is a living eye…his gaze pierces straight to the heart of truths in everything."

The critic Jean Paulhan put it another way, "this man has more than two eyes."

Brassaï’s was born Halász Gyula in Braşov, Hungary in 1899 to an Armenian mother and Hungarian father. As a child they lived in Paris while his father taught at the Sorbonne but in the 1910s the family resettled in Budapest. There the young man studied painting and sculpture at the Academy of Fine Arts until he enlisted in the Austro-Hungarian cavalry to fight in the First World War.

After the war, and with Hungary in shambles, he moved to Paris. In 1929, when he became interested in photography he turned to fellow Hungarian immigrant André Kertész to teach him the medium. Around this time he realized that Halász Gyula was not a good name for an artist so he took on the name, "Brassaï" which in Hungarian means "from Braşov."

With the publication of Paris de nuit the name "Brassaï" became famous and he was soon mingling with high society, photographing intellectuals, politicians and the wealthy. This new fame also enhanced his status with his circle of café pals, including Salvador Dalí, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Alberto Giacometti and Jean Genet.

"I need the subject to be as conscious as possible that he is taking part in an event… I need his active participation..."

Brassaï was at ease with all types of people and this played an important role in his photography. In the course of his nighttime perambulations he befriended pimps and streetwalkers, hoodlums and laborers, who allowed him to photograph freely among them. He was equally accepted photographing nude showgirls backstage at the Folies Begere as he was photographing prostitutes and their clients at Chez Suzy.

Paris by Night was also a technical achievement. In an era of slow lenses and even slower film, few photographers ventured out after dark. Brassï relished the darkness and by trial and error learned to get the night shots he was after. He invented ingenious tricks to help him, like gauging extended exposure times by how long it took for him to smoke a Gauloises.

At the end of his night’s shooting, he would return to his room at the Hôtel des Terrasses. Drawing the curtains, he turned the small space into a darkroom in which he would process his negatives and make prints. These prints were remarkable because of the richness of the darkness in them.

Using his training as a painter, Brassaï framed his shots so that small areas of light pierced large areas of blacks and shadows. Light reflected in wet streets and diffused by fog, would define shapes within the dark. This contrast gave his printed images richness and depth and he called these prints his "little boxes of night."

Cartier-Bresson neither processed his own film nor made his own prints. There were many other differences between the two men. Cartier-Bresson always shot with a 35mm Leica camera, working quickly and unobtrusively. He would shoot dozens of frames chasing his "decisive moment," his subjects all the while unaware of his presence.

In contrast, Brassaï shot with a large, fixed lens, 6.5x9 cm Voigtländer Bergheil folding camera. Brassaï mounted mounted the camera on a heavy wooden tripod. Although he shot with other cameras, like the Rollieflex, he never used a 35mm Leica, saying that he had no interest in taking dozens of shots of the same scene.

Also, unlike Cartier-Bresson he happily employed auxiliary lighting. For interior photographs like his café shots, he worked with an assistant who prepared a flash powder gun and a reflecting screen, while Brassaï chatted up and posed his subjects. The exploding flash powder produced a softer light than flashbulbs, giving the pictures their distinctive lighting. However, these powder explosions were so bright and loud that Picasso nicknamed Brassaï "the Terrorist."

Brassaï was never the distant observer Cartier-Bresson was. Not only were his subjects co-conspirators in the photos, they were his acquaintances. Brassaï wants us to like them: we are among friends. We are guests at the table.

Around the time of Paris du nuit’s publication, he joined with Hungarian immigrant Charles Rado to create the Rapho agency, one of the first press agencies specializing in humanistic photography. The new agency was a perfect fit for Brassaï, but his ability to travel to cover stories was limited.

In the ruins of war, Romania had subsumed Braşov and Brassaï’s Hungarian identity papers were invalid -- he was a stateless person. It wasn’t until 1949, a year after marrying the French citizen, Gilberte Boyer, that he became naturalized and could travel freely. This allowed him to work throughout the 1950s and 1960s shooting commercial assignments for magazines like Harper’s Bazaar.

In 1962, he gave up his commercial photography for sculpting but continued to exhibit and sell prints. He had his first international exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1948 and followed it with shows there in 1953, 1956, and 1968. He was the guest of honor at the Rencontres d'Arles Festival in France in 1970. In all, he produced dozens of photography books and nearly 35,000 exposures. Today his negatives, prints and contact sheets are housed at the George Pompidou Center in Paris. He died in 1984 in southern France near Nice.

Brassaï once summed up his photography by saying:

"Basically, my work has been one long reportage on human life."