Disruption, innovation, and the future of photography: Roger Cicala reads the tea leaves

posted Wednesday, February 19, 2014 at 7:54 PM EDT

Technology changes tend to be of two types: incremental improvements or disruptive innovations. Incremental improvements allow one manufacturer to take market share from another, and give the fanboys fuel for their Internet forum battles. Disruptive innovations may create a million new customers -- or make a million potential customers leave for some new hobby or way of doing things.

People love incremental improvements, but they often dislike disruptive innovations at first. Disruption causes major changes, and that can be threatening. It may be several generations before the new technology is clearly superior to what already exists, but eventually the disruptive innovation has a huge effect on the market. It causes some existing manufacturers to fail, others to flourish, and creates brand new manufacturers nearly overnight.

By my definitions, the Nikon D800 is a good example of a strong incremental innovation. Some photographers changed (or added) brands to shoot the D800, and Nikon increased their high-end DSLR sales for a while. But the DSLR market as a whole didn't change because of the D800. Nikon did a little better for a while, other manufacturers did a little worse, but there weren't any massive changes.

Cell phone cameras and social media were certainly a disruptive innovation. Depending upon your point of view, they've either cut the photography market severely or increased it amazingly. If you are a point-and-shoot manufacturer, the photography market is disappearing. If you own Instagram or Facebook, it's growing -- and phenomenally so.

For over a decade, the photography market has had one incremental improvement after another: increased pixel density, better high ISO performance, improved autofocus, and sharper lenses. But I think there's more disruption going on right now than simply cell phone cameras.

Most people, though, don't realize what a disruptive innovation first looks like. They expect a burning bush of technological triumph that's instantly recognizable as the next great thing. Historically, that's not what a new disruptive innovation looks like at all.

What Disruptive Technology Looks Like

It's Often the Tortoise, not the Hare

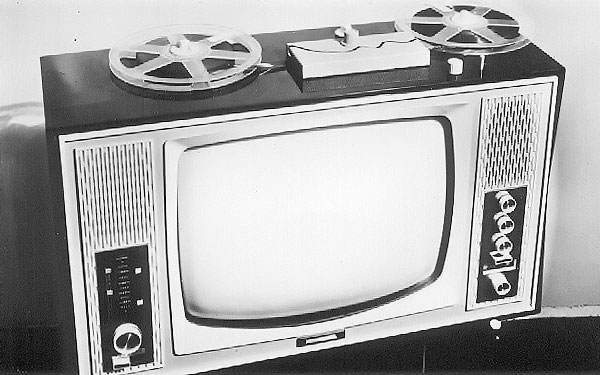

A new technology developed and introduced by company A often makes a fortune two years later for company B. The first home video recorder was introduced by the Nottingham Electric Valve Company in 1963. Avco introduced Cartrivision, the video recorder that first allowed you to rent major motion pictures to play in your home, way back in 1972.

But it was Sony and JVC that became hugely successful with home video recorders, and Blockbuster that made a fortune renting videos. This pattern -- that the company introducing the technology is often not the one which makes it successful -- is fairly frequent. Looking back, though, we don't notice it. Most people think of the early days of video recorders as a battle between Beta and VHS.

Original image source unknown.

Disruption Doesn't Occur Immediately

There's often a long delay between the introduction of a disruptive technology and its wide acceptance. In the example above, JVC and Sony made a fortune with video recorders, but not until a full decade after the Telcan was introduced. Blockbuster rented its first videos a decade after Avco's Cartrivision.

Often this is because the new technology comes in an unacceptable package. Nottingham Electric's Telcan was a reel-to-reel system that recorded only 15 to 20 minutes of black-and-white video. Avco's rentals took several days to arrive and the cartridges were rewind-disabled -- you got to view the movie once, and only once. Can you believe a manufacturer would go to the trouble of disabling a feature to try to increase sales?

The pattern is repeated frequently. Xerox originated the computer mouse and graphical user interface, and used them on its Alto computers and Star workstations in the 1970s. Apple borrowed them for the successful Macintosh nearly a decade later. Microsoft, in turn, used them for the even-more successful Windows.

Disruption Isn't Recognized at First

Being different, less polished, and geared towards a new marketplace, a disruptive technology is often disregarded at first. Those invested in the status quo often ridicule it. When GUI-based computers were introduced, existing computer users laughed at them. Who in the world would want a computer that you couldn't program yourself? The people buying them shouldn't be allowed to have a computer -- they didn't even know how to operate a command-line interface!

When George Eastman mass produced dry plate film in 1878, most photographers thought it useless. Any photographer worth his lens made his own wet plates, developed them, and printed them. When Charles Dodson (aka Lewis Carroll) first saw dry plates, he spoke for most professional photographers when he said, "Here comes the rabble." Within a decade, film dominated photography -- not because existing professionals flocked to it, but because so many new photographers entered the field that wet-plate photographers couldn't compete.

My point is that when looking at innovative and disruptive technologies, we should realize three things: The introduction doesn't always shake up the market; that usually comes later. The introducing company isn't always the one that succeeds with the new technology. Many people invested in the market's status quo either don't recognize a disruptive technology, or despise it.

Disruptive Photography Innovations

The collodion process, dry-plate film, roll film, 35mm film, rangefinders, SLRs and a dozen other disruptive innovations all rocked the market place. Each increased the number of people who considered themselves photographers. During each innovation, existing photographers dismissed the new innovations as ruining their art. Some companies thrived with change while others missed the boat completely.

Autofocus is a fairly recent example that followed the usual pattern. Leica originally developed phase-detection autofocus in the 1960s. They didn't see much use for it, and sold the technology to Honeywell. Konica was first to mass-produce an autofocus camera, licensing Honeywell's Visitronic phase-detection technology for 1977's point-and-shoot Konica C35 AF. Others tried to get around Honeywell's patents with alternative autofocus methods, such as the ultrasonic sonar system of the Polaroid SX-70 Sonar Autofocus, and the near-infrared autofocus of the Canon Sure Shot.

Image courtesy of Spinal83 / Wikipedia, used under a CC-BY-SA 3.0 license.

And in 1981, Pentax came out with the first camera using a separate phase-detect autofocus sensor illuminated by a sub mirror, as still found in modern DSLRs. Not surprisingly, the Pentax ME F never caught on, doomed by its groundbreaking and yet extremely slow, inaccurate autofocus system. Only a single lens compatible with the system -- and marred by a large battery compartment beneath the lens barrel -- was ever released.

Nor was Nikon any more successful with its first attempt at a phase-detect SLR two years later, even though it focused rather more quickly. The Nikon F3AF was expensive, still rather slow to focus, and required a chunky autofocus viewfinder accessory. While the manual-focus variant, the Nikon F3, was a smashing success, the F3AF was not.

If you can find a working Pentax ME F or Nikon F3AF system with autofocus accessories at a garage sale, you'll do very well on eBay.

Public domain image courtesy of Paolo Beccaria / Wikipedia.

Real photographers laughed at all of this the clumsy technology in the early 1980s. It was obvious that autofocus would never be fast enough for something like sports, where the subject was moving. Only manual focus and a skilled photographer could possibly capture action images.

The first camera to find huge success with phase-detection autofocus was the Minolta Maxxum 7000, released in 1985. For a short time Minolta was king, but it may have found itself wishing it had been rather less successful. Honeywell sued --and eventually won -- over the design of the AF system used in the Maxxum 7000.

Minolta eventually had to pay US$127.6 million in damages and penalties, Honeywell's trial costs and other expenses, not to mention the time and money it had put into its own unsuccessful defense. And in the meantime, Canon, Nikon, and Pentax had followed up with successful phase-detection based cameras of their own. By the 1990s, companies who made 35mm cameras without phase detection were mostly going bankrupt. Within a decade, Minolta itself would be no more. The company merged with one-time rival Konica in 2003, and the newly-combined entity soon sold its photo division to Sony.

Digital is another good example. You probably know Kodak developed the first digital camera and released the first digital SLR, the DCS 100, back in 1991. Based on a Nikon F3 body with a Kodak external storage unit, it sold for $13,000 and provided a whopping 1.3 megapixel image. It wasn't a huge success.

Image courtesy Gruenemann / Flickr. Used under a CC-BY 2.0 license.

Minolta also introduced the first portable digital SLR back in 1995. The RD 175 used three separate 0.38-megapixel CCD image sensors, combining and interpolating their images in-camera to yield a final 1.75-megapixel output image. Instead of a bulky storage unit like that needed by Kodak, images were stored on PCMCIA cards. Canon introduced its first mainstream digital camera, the PowerShot 600, the following year. It would be another four years before the company launched the first truly affordable DSLR, the EOS D30. Nikon, meanwhile, launched its mainstream Coolpix lineup with the Coolpix 100 in 1997.

Image courtesy of Rama / Wikipedia. Used under a CeCILL license.

Photographers of the late 1990s, of course, talked loudly and often about how digital images could never replace the performance and resolution of film. Those digital things might be fine for vacation snapshots, but not for a professional photographer or serious amateur.

The transition to digital was truly disruptive. Some manufacturers thrived during the digital transition. Despite releasing the first good autofocus SLR and the first portable digital SLR, Minolta wasn't one of them. Bronica, Contax, Kodak and Polaroid were also left behind. Canon and Nikon did very well. A few companies, like Panasonic, Samsung and Sony entered the market for the first time.

Today's Disruptive Photography Innovations

Interchangeable-lens shooters who started their photographic careers since the start of the millennium won't have noticed much in the way of disruptive innovations. Canon and Nikon have steadily brought out enough incremental improvements to keep them dominant in the world of SLRs. Sure, there have been a number of technologies that were leaps rather than simple improvements: mirrorless cameras and the Micro Four Thirds format, Foveon sensors, and fixed-lens, large sensor cameras, among others. None of them has really disrupted the marketplace though -- at least, not yet.

The Obvious Disruptive Innovation

I don't think anyone will argue that cell phone cameras and social media have disrupted the photography market. They came from outside the mainstream photography world, and attracted a new set of consumers to a new market. Let's call them picture-takers since most of us don't consider them photographers. Call them whatever you want, but there are a lot of companies in the image hosting and online-printing worlds that call them a huge customer base.

The effect of cameraphones on the existing photography marketplace was mostly negative. Many point-and-shoot companies exited the imaging business. Others, like Fuji, Olympus, and Sony had to migrate to the more serious camera market. The disruption also affected Canon and Nikon -- they can no longer get customers to buy their point and shoot cameras today in the hope that they'll migrate up to SLRs in a few years. Only one manufacturer today is attracting a huge number of entry-level customers which it might move up to serious cameras -- and not courtesy of its compact models. That would be Samsung, maker of one third of the world's smartphones according to market research firm Strategy Analytics.

Other Disruptive Innovations

If your first thought when you read one of these is 'but it's not as good as existing technology', then remember the examples above. Photographers laughed at autofocus because it was too slow and inaccurate. They laughed at digital because it could never resolve as well as film. They're still laughing at cell phone cameras as useless toys -- and then they set down their SLRs to take a cell phone picture that they can upload immediately.

Mirrorless technology

I know. Mirrorless isn't growing in most of the world. Lens selection is still rather limited. Neither Canon nor Nikon are pushing their way in very hard. The initial reason for the existence of mirrorless -- smaller, more portable camera systems -- appeals to only a subset of photographers.

I think that the disruptive effects of mirrorless on the marketplace are still to come. I think it's disruptive because a mirrorless camera is far simpler than an SLR camera. That, eventually, means less expensive, more reliable, and quicker to change.

Compare a teardown of a mirrorless camera with an SLR. Here are a few key takeaways:

- The SLR has a complex electromechanical mirrorbox assembly.

- The mirrorbox assembly has a lot of mechanical, moving parts that a mirrorless camera doesn't have. Mechanical, moving parts sometimes fail. The manufacturer has to include the cost of warranty repairs when they determine what price a camera should sell at.

- The SLR has a secondary mirror that must be perfectly aligned with the phase detection AF assembly.

- The phase detection AF assembly must be electronically calibrated and mechanically aligned to the sensor, mirror and viewfinder.

As an added thought, once electronic shutters become adequate, a mirrorless camera would have no moving parts except for buttons and dials. Electronic shutters aren't quite ready for prime time on CMOS sensors, but they are getting close.

Simpler design makes things easier to change and modify. When I disassembled the Sony A7R, I saw that the grip is held on by a single large screw. My first thought was just how simple it would be to put the screw on the front of the grip, offer three grip sizes, and let the owner change grips to better fit their hand.

Most current mirrorless cameras have a short backfocus distance -- the distance between the lens mount and the sensor -- but that's certainly not necessary. The Pentax K-01 mirrorless camera had the same backfocus distance as do the company's SLR cameras, and used the exact same lenses without an adapter. Nikon or Canon could make a full-frame mirrorless camera with the same backfocus distance as their DSLRs, which would let their customers use the entire, existing lens lineup.

I know that mirrorless technology hasn't been disruptive yet, but I think it will become disruptive with further incremental improvements in two other technologies.

Improved Autofocus Technology

Autofocus technology has been incrementally improving for several years. Many of these autofocus improvements, like on-sensor phase detection, hybrid contrast / phase detection autofocus, and improved contrast detection algorithms are steadily eliminating one of the major detractions from mirrorless cameras -- that the autofocus is slow.

Phase detection is also being improved, though, and that may keep DSLR autofocus superior in some ways. Will contrast-detection AF ever be as good as phase detection for sports or birds-in-flight? Perhaps not. But its definitely getting better and clearly is simpler, more accurate, more reliable, and less expensive.

It may be that we'll see 'action photography' cameras with 10 frames-per-second burst capture and phase-detection AF as separate from 'general-purpose' cameras with half the burst rate, contrast or hybrid autofocus, and focus peaking for manual focus lenses. Some photographers will prefer one, some the other. Assuming the cameras use the same lens mount, a lot of people might own both.

Electronic Viewfinders

Electronic viewfinders aren't quite up to the same standards as optical viewfinder yet. But like most electronic devices, they're improving noticeably with every generation. I assume they'll be getting less expensive over time, too; electronic devices tend to do that. EVFs do still have some disadvantages over optical, but they have some advantages, too, and the disadvantages are decreasing.

Third-party lenses

A second disruptive innovation, in my opinion, started around 2005 when Zeiss started marketing their very good lenses in SLR mounts. It may not seem like this was huge news; after all, manual focus prime lenses aren't the mainstay of many photographers' kit. But it was a big deal. The very best lens at certain focal lengths were no longer always the manufacturer's own lens. Now Sigma, Tamron, Voigtländer and Samyang, among others, make lenses that are nearly as good -- and sometimes better -- than the manufacturer's lenses, and sell them at a lower price.

You may think 'that's not disruptive'. I think it is, though, because it affects the existing SLR business model. Manufacturers didn't mind selling SLRs at near-break even, because they made money selling lenses. Now the camera companies are getting hit from both sides. They can't attract young customers to their point-and-shoots because of smartphones. Yet their existing customers are now less likely to by the manufacturer's lenses.

You may not be buying third-party lenses, but a lot of people are. I recently bought a Pentax K3 outfit. The only Pentax lens I bought along with it was the 300mm f/4. My other three Pentax mount lenses are third party. For my Canon 6D I have three Canon and two third-party lenses. It's not just me, a recent poll on one of the major camera forums showed more Canon owners shot the Sigma 35mm f/1.4 than the Canon 35mm f/1.4.

A Couple of Other Changes

There are two more things that I think are going to change the camera market over the next couple of years. I'm not sure it's appropriate to call them disruptive technologies. Maybe they're disruptive techniques.

Modularity

This is a trend I've been noticing with certain brands. If you want to get a comparison with modular versus non-modular lenses, you can look at this teardown comparison of 24-70 f/2.8 lenses. For a look at a really modular camera, here's a teardown of the Sony A7R. Basically a modular device quickly breaks down into a few major components, each of which can be further separated into individual parts. A non-modular device separates into lots of individual parts.

Why does it matter? For one thing it makes repairs vastly simpler. Rather than stocking hundreds of parts for each lens and camera, the repair center may just stock a few modules and a few other parts. Inventory control for 1,000 spare shutter modules is a lot simpler (and therefore cheaper) than it would be to keep 200 to 1,000 of each of the 22 parts that make up the shutter module.

Sure, the shutter module in the Sony A7R costs more than the individual gear or capacitor that may be broken, but replacing the module takes 30 minutes, compared to two hours to replace the gear and recalibrate the shutter. The labor and inventory savings more than offset the increased price of the module over that of the part.

Modularity can make upgrades and improvements easier and faster, and it may also allow some customization for cameras. Since I used the A7R as an example, let's pretend that some people don't like the shutter. That might mean that they'd wait 18 months or two years to see if the next version of the camera has a better shutter. But with a modular design like this, Sony could just call Copal -- who makes the shutter module -- get them to design a new shutter that fits in the existing space, and release a variant with a more appealing shutter just a few months later.

Or maybe some entrepreneur will figure out a way to put some shock-absorbing mounts on that shutter. (Currently, it has metal-to-metal mounts). Getting to that area in such a modular camera would be much simpler than it would in a standard SLR, perhaps making a modification cost-effective. A new viewfinder, body shell, different grip, or different sensor would require only a new module, and not a complete redesign.

Not everyone is going modular, at least not yet. Sony cameras particularly -- and mirrorless cameras in general -- are getting more modular. DSLRs are not. Newer Canon and Zeiss lenses are modular. Tamron and Sigma lenses are too, but to a lesser degree. If anyone else's lenses are more modular I haven't yet noticed it.

Service and Repair

Factory service has changed a lot over the last two years. I deal with several thousand repairs per year here at LensRentals, so I notice these changes. Some of the changes I despise: forcing independent repair shops to close, refusing to sell parts, and finding excuses to not honor warranties, for example. Thirty-day turnaround times are awful, too.

But for every action, there's a reaction. A number of companies decided that offering good service was a way to attract customers. Tamron, for example, offers a refurbished lens if they can't fix your lens within three business days. Sony has recently offered brand-new items as replacements when a part is on backorder.

There is one recent repair trend that I think is going to become more common: exchange repairs. You send the lens or camera in for repair. The company charges for the repair, but sends you a new or refurbished item in place of your broken one. The broken item gets sent to a central service center where it is either refurbished or broken down to component parts. Rokinon and Zeiss in the USA already do this for (as best I know) all repairs. Several other companies have started doing it for certain repairs.

Exchange repair allows smaller companies to offer service as good or better as the huge companies. Canon and Nikon each have several factory service centers in the U. S. and dozens of other centers across the world. A smaller company can't compete with that, but they can put an exchange center in every country and build one large service center to salvage parts and refurbish items. Exchange is quick and simple and most people I've talked to prefer it.

Conclusion

History suggests two things pretty strongly. The first is that when change comes, people invested in the status quo (that would be us photographers, when discussing the photography market) have a strong desire to deny it. Things have never been better. There is no need for change. And this is a stupid change that nobody would ever want. Well, nobody who is serious about photography would want it.

For example, you may think the Sony A7R is a horrible camera: there are few available lenses, shutter vibration may be an issue, you might hate that it's so small, or maybe dislike the viewfinder. So, you dismiss it. Just like people dismissed the first Pentax SLR with phase-detection AF, or digital imaging on the RD-175. Whether the A7R is successful or not has no more meaning than whether the Minolta RD-175 was successful or not. Digital cameras took over anyway, and the same may be true of mirrorless cameras.

The second thing history suggests is that there's no accurate way to guess which companies are going to thrive and which will fail during a time of disruption. If being first were a huge advantage, we'd all be shooting Minolta digital SLRs. If being the biggest or most profitable were a huge advantage, we'd all be shooting Kodak or Polaroid. Sometimes biggest is really a disadvantage. As they say, it takes a long time to turn a battleship.

When the changes start rolling, though, they roll fast. Ask the video guys how many were shooting RED or Blackmagic cameras back in 2006. (The answer is none; there were no RED or Blackmagic cameras in 2006. Now they are everywhere.)

Is there a reason I use video cameras as an example in a photography article? Sure there is. Those two video cameras don't need mirrorboxes, don't use phase detection autofocus, are very modular, and can be purchased with different lens mounts. Which fits in nicely with my speculation.

My Speculation

Full-frame mirrorless cameras are here, so that part isn't speculation. The death of point-and-shoot cameras is already happening, so that's not speculation, either. Let me speculate that the following things will also occur (big assumptions, but not ridiculous ones.)

- Either on-sensor phase detection or contrast detection autofocus becomes fast enough for most photographers (seems very likely).

- Modular designs become widespread (maybe, maybe not).

- Electronic viewfinders become good enough for most photographers (seems very likely).

- Electronic shutters become a viable reality (likely, but maybe a few years away).

- Modularity and 'exchange repairs' make good service possible for even a startup company (it can if they want to).

- Third-party lens manufacturers continue to make excellent optics at lower prices (seems certain).

A sensor with contrast detection autofocus and an electronic shutter is very nearly a camera-on-a-chip. The sensor manufacturer could sell it to a dozen companies who each design their own camera around it. New camera brands might appear overnight.

A camera might be offered in various option packages. Different housings, an additional mechanical shutter for those that need it, an electronic viewfinder if you want it, or no viewfinder if you always shoot tethered in the studio. I order my computers online with a number of different options and get them three days later. I wouldn't mind doing the same thing with my next camera.

If the AF system is contrast detection, then a manufacturer doesn't have to worry about hundreds of phase detection AF algorithms for various lenses. Contrast detection is lens-agnostic. Joe's camera company might make the same camera available in Nikon F-mount, Canon EF-mount, or Sony E-mount.

You can already do that with a RED camera. I serve as a lens consultant for a few well known photographers who shoot magazine spreads on RED Epics and Dragons for the simple reason that they can shoot Leica, Canon, or Nikon lenses with a simple mount change done in the field. They want to use the different lenses. They don't want to remember the controls or have to match color differences on three different cameras.

Third-party lens makers seem to be in a very good position right now. It's become apparent that they are making very high-quality glass at a price well below the major camera manufacturers. If part of that price difference is because the camera manufacturers have to price their lenses to support their camera sales, then the manufacturers have a major problem.

Two factors have historically held back enthusiasm about third-party lenses: inaccurate autofocus and poor service or quality control. Third-party service is now at least as good as the major manufacturers, if not better. A contrast-detection based autofocus system is just as accurate with a third-party lens as it is with a manufacturer's lens, or can be if the lens was designed for contrast detection.

I certainly don't know who will thrive and who will fail as things change. And I sure wouldn't rush out and change brands over it. Everything we shoot with today will still be working fine in a few years. Sure, Joe's cameras may release something you just have to have, but I'll bet it mounts some existing lenses. I expect most of the third-party lens makers will follow Sigma's lead and be willing to change your lens mounts for you.

That's the nice thing about disruptive technology. It always gives the consumer more choice. Most consumers will embrace it, eventually, like they did with autofocus and digital cameras. A few will sit around and talk about how it was back in the good old days, when men were made of iron and ships of wood.

(Teacup image courtesy of SodanieChea / Flickr. Used under a CC BY 2.0 license. Roger Cicala is the founder of LensRentals.com. Visit LensRentals.com to rent that cool lens you've been hankering for, and for some of the best customer service on the Internet!)