New imaging technology claims to be 12 times as color-sensitive as conventional sensors

posted Tuesday, October 7, 2014 at 9:56 AM EDT

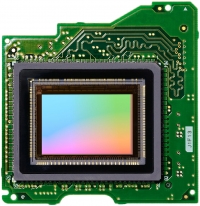

Most digital imaging sensors work similar to the human eye, in that they are sensitive to the three primary colors red, green and blue. While there are differences in their individual design (most notably between classic Bayer pattern sensors, Sigma's three-layer Foveon sensors and Fujifilm's X-Trans sensor), the basic principle remains the same.

The problem with conventional sensors, however, is that their individual pixels are sensitive only to specific wavelengths of light, as they are covered by either a red, green or blue color filter. This means that a lot of incoming light is lost, and also that not all wavelengths of the visible light get picked up. A new technology developed by researchers at the Universities of Granada, Spain and Polytechnic University of Milan, Italy aims to change that.

The imaging system developed in Granada and Milan will be able to pick up "full color information" at each photosite, according to an official announcement of the University of Granada. More precisely, it will be able to distinguish 36 individual color channels, which would be twelve times the color accuracy of a conventional sensor -- or the human eye.

This feat is achieved by the so-called Transverse Field Detectors that the imaging system is based on. They make use of the fact that different wavelengths of light penetrate the silicon structure of a sensor to different depths -- much like Sigma's Foveon X3 three-layer sensor. The difference between the Foveon sensor and the new technology, however, is that the latter has a much wider color spectrum than Sigma's sensor.

Image courtesy of Miguel Ángel Martínez Domingo

The Transverse Field Detectors do not require any form of color filter, as they can be precisely tuned to detect a photon's wavelength and thus extrapolate much more color information out of a single photosite than would be possible with a conventional sensor. Whether they are limited to detecting only the wavelengths of visible light, or whether they are also sensitive to infrared and ultraviolet wavelengths was not stated in the announcement.

Now the question is, what kind of applications is a sensor like this suited for? So far, the researchers see it used in medical imaging, remote sensing, satellite images, military and defense technology, industrial applications, robotic vision, assisted or automatic driving "and a long etcetera of potential uses." Upon inquiry, Miguel Ángel Martínez Domingo, one of the researchers that developed the new imaging technology, mentions that there is definitely also a potential use in classic photography.

We'd reckon that it could be well-suited for portrait or landscape photography, where the additional color information might actually be a great benefit as it would allow for much more precise retouching and color fine-tuning. Another possible scenario where the TFD sensor might provide a benefit are mixed light and artificial light scenarios, which are notoriously difficult to handle for conventional sensors.

However, at this time it's impossible to say if or when we're going to see this new technology implemented photographic products.

(via Vice Motherboard)