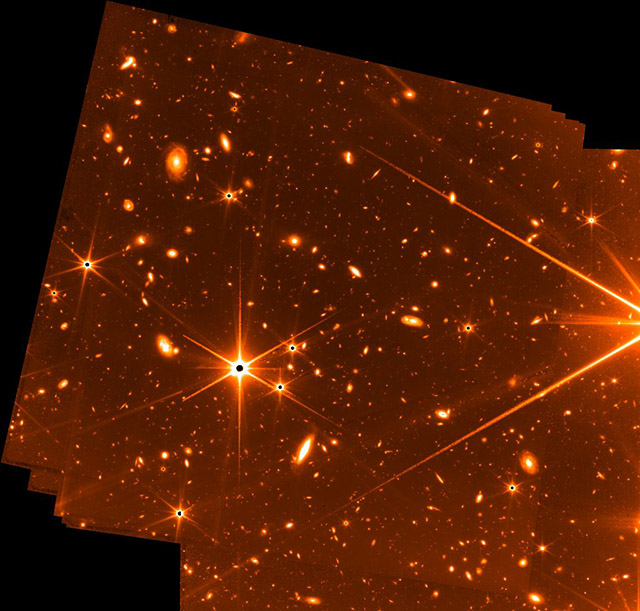

Just days away from James Webb Space Telescope’s debut photos, NASA shares test shot that’s one of the deepest images of the universe ever captured

posted Thursday, July 7, 2022 at 12:30 PM EDT

NASA will release the first full-color images captured by the James Webb Space Telescope on July 12. It's right around the corner. However, NASA has provided a new test image to help whet our collective appetite. It's only a test image, but it's still a neat look behind the scenes. Better yet, it's currently the deepest image ever captured of the universe – at least until next Tuesday.

The photo was captured in May by Webb's Fine Guidance Sensor (FGS). Developed by the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), the FGA's primary purpose is to enable "accurate science measurements and imaging with precision pointing." However, the FGS can also capture images. There's limited bandwidth available to transmit data from Webb at L2 to Earth, so FGS images are often discarded. But bandwidth was available during a stability test, so the team retrieved captured data from the FGS.

The image below is a little rough around the edges. The instrument isn't optimized for scientific observation but is used to help the telescope's primary four scientific instruments stay on target. The FGS doesn't have color filters, so that's why the image is monochromatic. The six diffraction spikes around the bright stars are due to Webb's six-sided mirror segments. Beyond the stars, you can see many galaxies. Some of these faint blobs will be investigated by Webb.

"This Fine Guidance Sensor test image was acquired in parallel with NIRCam imaging of the star HD147980 over a period of eight days at the beginning of May. This engineering image represents a total of 32 hours of exposure time at several overlapping pointings of the Guider 2 channel. The observations were not optimized for detection of faint objects, but nevertheless the image captures extremely faint objects and is, for now, the deepest image of the infrared sky. The unfiltered wavelength response of the guider, from 0.6 to 5 micrometers, helps provide this extreme sensitivity. The image is mono-chromatic and is displayed in false color with white-yellow-orange-red representing the progression from brightest to dimmest. The bright star (at 9.3 magnitude) on the right hand edge is 2MASS 16235798+2826079. There are only a handful of stars in this image – distinguished by their diffraction spikes. The rest of the objects are thousands of faint galaxies, some in the nearby universe, but many, many more in the distant universe. Credit: NASA, CSA, and FGS team."

Credit: NASA, CSA, and FGS team

Neil Rowlands, program scientist for Webb's Fine Guidance Sensor at Honeywell Aerospace, said, "With the Webb telescope achieving better-than-expected image quality, early in commissioning we intentionally defocused the guiders by a small amount to help ensure they met their performance requirements. When this image was taken, I was thrilled to clearly see all the detailed structure in these faint galaxies. Given what we now know is possible with deep broad-band guider images, perhaps such images, taken in parallel with other observations where feasible, could prove scientifically useful in the future."

Jane Rigby, Webb's operations scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland added, "The faintest blobs in this image are exactly the types of faint galaxies that Webb will study in its first year of science operations."

Since the FGS isn't designed for scientific observation, some of its characteristics are unique. The first full-color science images we see next Tuesday will be higher-quality, not monochromatic, and show even better detail. Of the test image, NASA writes, "The FGS image is colored using the same reddish color scheme that has been applied to Webb’s other engineering images throughout commissioning. In addition, there was no “dithering” during these exposures. Dithering is when the telescope repositions slightly between each exposure. In addition, the centers of bright stars appear black because they saturate Webb’s detectors, and the pointing of the telescope didn’t change over the exposures to capture the center from different pixels within the camera’s detectors. The overlapping frames of the different exposures can also be seen at the image’s edges and corners."

While the FGS has its moment in the spotlight for now, once July 12 rolls around, we will likely never see images from the onboard guidance instrument again. That said, every image the James Webb Space Telescope captures is possible due to the behind-the-scenes work performed by the FGS. It has already played a critical role in helping scientists align Webb's instruments, but it will also help Webb capture every subsequent image throughout the entire mission.

Be sure to stay tuned on July 12, as we'll share and discuss Webb's first scientific images.