Photographers on Photography: The D-Day Landing and Robert Capa’s Slightly Out of Focus Legacy

posted Wednesday, June 6, 2012 at 11:10 AM EDT

(Editor's note: The following piece is part of our new "Photographers on Photography" series. It commemorates the D-Day landing at Normandy that occured 68 years ago on this day and photographer Robert Capa's role in covering it. The quotes are taken from Capa’s book “Slightly Out of Focus” and the author's personal sources: Milt Felsen and Cornell Capa)

(Editor's note: The following piece is part of our new "Photographers on Photography" series. It commemorates the D-Day landing at Normandy that occured 68 years ago on this day and photographer Robert Capa's role in covering it. The quotes are taken from Capa’s book “Slightly Out of Focus” and the author's personal sources: Milt Felsen and Cornell Capa)

“It’s not easy always to stand aside and be unable to do anything except record the suffering around one. The last day some of the best ones die. But those alive fast forget.”

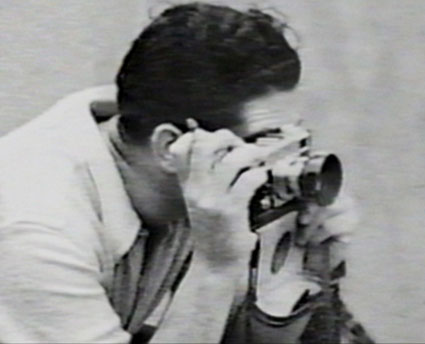

Sixty-eight years ago, on June 6, 1944, the Hungarian born photographer Robert Capa waded ashore on the beaches of Normandy with two Contax cameras wrapped in oilskins tucked into the folds of his jacket.

“It was still very early and very gray for good pictures, but the gray water and the gray sky made the men, dodging under the surrealistic designs of Hitler’s anti-invasion brain trust, very effective.”

“I crawled on my stomach over to my friend Larry the Irish padre of the regiment…hell he growled…comforted by religion, I took out my Contax camera and began to shoot without raising my head.”

In his short life, Robert Capa covered five wars and when he died in 1954, he was in the combat zone covering the end of the France’s war in Indochina; a war that was soon to become America’s. Walking away from his jeep that day, he stepped on a landmine and died at age 41.

Capa had first photographed war in 1936 when he, like Ernest Hemingway and so many others, was drawn to the Spanish Civil War, the first conflict with European fascism. It was there he took a controversial photo of the moment of death of a Spanish partisan fighter. While there has been some controversy over its authenticity, few deny its impact. My friend Milt Felsen was an ambulance driver in Spain with the volunteers of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade.

In 1936, he met Capa: “He’d hitch a ride to the front with me every so often, always asking where the action was. He was always there. But when I’d meet him in Madrid, he was always dressed to the nines and I never saw him without a pretty mam’selle on his arm. He was a good man.”

Capa famously said that, “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you aren’t close enough.”

That D-Day morning he was close enough.

“The water was cold and the beach still a hundred yards away. The bullets tore holes in the water around me, and I made for the nearest steel obstacle. A soldier got there at the same time, and for a few minutes we shared its cover.”

Under German bombardment, against all odds, Capa took some of the most memorable war photographs ever made.

“The next shell fell even closer. I didn’t dare to take my eyes off the finder of my Contax and frantically shot frame after frame. Half a minute later, my camera jammed—my roll was finished. I reached into my bag for a new roll, and my wet, shaking hands ruined the roll before I could insert it in my camera.”

“I paused for a moment…and then I had it bad. The empty camera trembled in my hands.”

“The rip tide hit my body and every wave slapped my face under my helmet. I held my cameras high over my head...and told myself, “I am just going to dry my hands on that boat.”

Capa reached the landing craft, but as he hauled himself on board, there was an explosion that covered him in blood and feathers. The feathers had come from the sailors’ blown apart kapok jackets. Making his way across the bloody deck, he reached the engine room and dried his hands by the engine’s warmth.

“...put fresh film in both cameras. I got up on deck again in time to take one last picture of the smoke covered beach…An invasion barge came alongside…the transfer of the badly wounded in the heavy seas was a difficult business. I took no more pictures, I was busy lifting stretchers.”

Over Capa’s head, a fresh faced kid from Brooklyn jumped into the flack-filled, cloud-muddied skies. He was my wife’s uncle and it was his first taste of war. He made it to the ground, fought his way halfway to Berlin and returned home safely.

Capa took that invasion barge back to England and discovered that he was the first photographer to return with pictures. Offered a chance to go to London for an interview, he refused. After putting his film in a press bag and sending it by courier for processing, he changed his clothes and returned to the beaches of Normandy on the first available boat.

A week later, he learned that the pictures he had taken were considered the best images anyone had made of the invasion. However, an excited darkroom assistant, while drying the negatives had used on too much heat causing the film emulsion to melt before his eyes, running down the hanging strips before he could do anything. Out of the one hundred and six images Capa had taken only eight survived.

Yet, when those few photos were published around the world, they caused a sensation. They were first photographs taken from the inside of a war, from the midst of a great battle. The faulty drying too had somehow added a special quality to them, one that lifts them out of that specific time and place, making them universal images of war.

Many publications added a caption to these photos, to explain to readers why they were blurred and slightly out of focus. It read simply: “Capa’s hands were badly shaking.”