The extraordinary story behind the iconic image of Che Guevara and the photographer who took it

posted Thursday, June 6, 2013 at 4:51 PM EDT

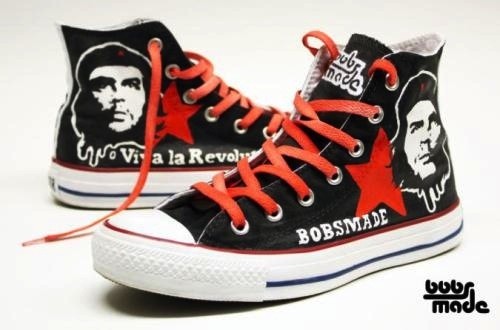

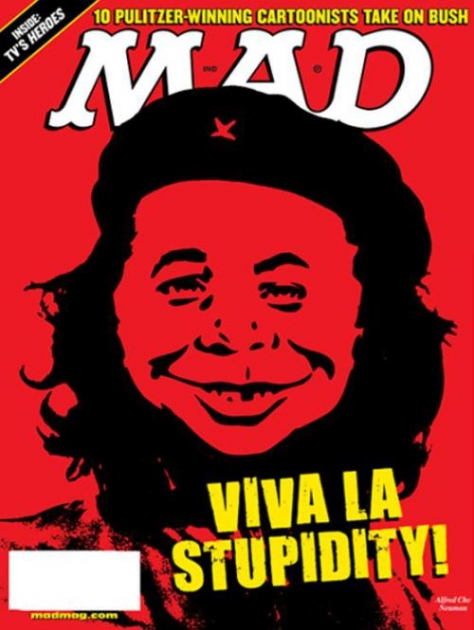

Cuban photographer Alberto Korda's photo of Che Guevara has been emblazoned on posters, t-shirts, diapers, playing cards and almost everything imaginable. Today, the Che image is well over 50 years old and is still as popular and as marketable as ever.

"Strolling down Brunswick Street or Chapel Street (in Brisbane), it could be easy to think Che Guevara was the only man under 40 never to have worn a Che Guevara T-shirt." -- Richard Castle in The Brisbane Times.

It should have made Korda rich and famous, but it didn't. In fact it was almost forgotten for years. The journey of Che's photograph is a remarkable voyage through the murky waters of communism and capitalism.

The photographer

Alberto Diaz Gutiérrez was born in Havana in 1928 and learned photography as a studio assistant shooting weddings, baptisms and funerals. In 1953, he opened his own studio and he changed his name to Alberto Korda. Within a few years Studio Kordas was the premiere fashion photography studio in Cuba. Korda would later admit that he chose a career in fashion photography because his "main aim was to meet women."

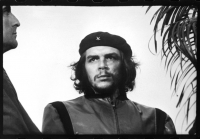

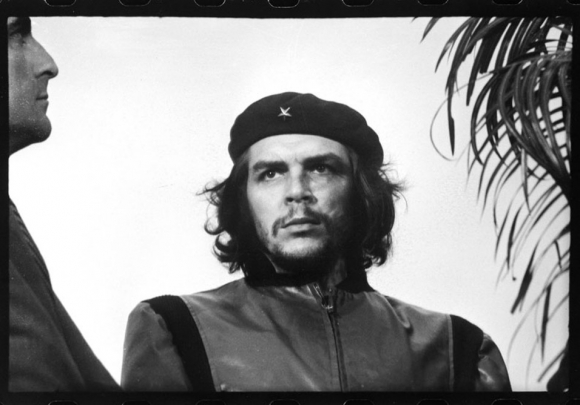

Alberto Korda holding the negative of the world's most iconic image.

Korda’s success in fashion photography came to abrupt end in 1959 when, as he recounted, "Nearing 30, I was heading toward a frivolous life when an exceptional event transformed my life: the Cuban Revolution." Fidel Castro and Ernesto "Che" Guevara rode triumphantly into Havana in January of that year, and with their arrival Korda the fashion photographer became the Revolution's photographer and Castro's friend.

The moment

The Che image was made on March 5, 1960, at a funeral service for the 136 people who were killed when a French ship carrying arms to Havana was sabotaged and blown-up. Crowds filled the street of Havana, and Korda was there working for the newspaper Revolución. As Castro’s funeral oration droned on Korda approached the speakers' platform. With Castro were other leaders of the revolution, the French writers Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, and, of course, Che. When Korda got close to the platform, he noticed that Che -- who had been standing in the back of the stage -- had moved forward.

"I remember his staring over the crowd on 23rd street," Korda says. Staring up, he was struck by Guevara's expression which he says showed, "absolute implacability," as well as anger and pain. Korda was shooting a Leica M2 loaded with Plus-X film and had a 90mm Leica telephoto lens mounted on it. He managed to take just two frames -- one vertical and one horizontal -- before Che stepped away.

Che Guevara, 1960 Photo by Alberto Korda.

When Korda returned to his studio, he processed the film and made several prints for Revolución. For the Che photo, he cropped the original frame into a vertical portrait to eliminate distracting elements.

Ironically, the newspaper didn't use the Che image, but instead chose a shot of Castro with Sartre and de Beauvoir. Years passed by and the photo languished on the wall of Korda’s studio, although he did make a few prints as gifts to friends.

The "viral" effect

This all changed one day in early 1967 when an Italian publisher, Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, came with a letter from the Cuban government asking Korda to help find him a portrait of Che. Korda pointed to the print hanging on the studio wall, saying that it was the best one he had ever taken of Che. Feltrinelli ordered two prints, and when he came to pick them up the next day, Korda said that as a friend of the revolution Feltrinelli did not have to pay for them.

From here things get strange, as the two prints began to go "viral," so to speak. First, mysteriously, the photo appeared in Paris Match magazine in August 1967 in an article titles "Les Guerrilleros." It was not credited and no one to this day knows how the magazine got hold of it. Then around the same time, an Irish artist named Jim Fitzpatrick used the image as the model for a color poster. Fitzpatrick claims that he got the photo from the Dutch anarchist group "The Provos," who said they got the photo from Sartre.

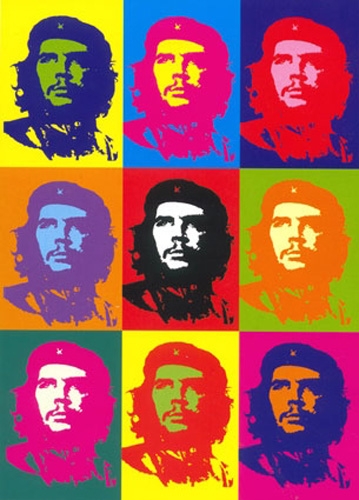

Che Guevara, 1968. Painting by Andy Warhol

The tipping point

But the tipping point for the image was in October 1967, when Che was executed in Bolivia. Demonstrations broke out around the world condemning the murder and Feltrinelli printed up thousands of Che posters and sold them to protesters. The photo was now called Guerrillero Heroico, and it next surfaced in 1968 on New York City subway billboards as a painting by artist Paul Davis advertising the February issue of the Evergreen Review magazine.

Because Fidel did not recognize or sign the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, neither Korda nor the Guevara family has earned anything from the billions of reproductions of the image. Without copyright protection, anyone could use it and the more it was seen, the more it got used.

In 2000, Korda sued Smirnoff, the Vodka company, for using the image in an advertisement, saying that, "As a supporter of the ideals for which Che Guevara died, I am not averse to its reproduction by those who wish to propagate his memory and the cause of social justice throughout the world, but I am categorically against the exploitation of Che's image for the promotion of products such as alcohol, or for any purpose that denigrates the reputation of Che."

Korda received an out-of-court settlement of $50,000, which he donated to the Cuban healthcare system, "If Che were still alive, he would have done the same," Korda said. But the case proved that Korda had completely lost control of the Che image and any uses.

With endless reuses for commercial and social purposes, the photo has become more of a graphic icon and has lost much of its individuality. However, simultaneously, it has also gained a certain universality. Shooting slightly upwards at Che -- who is looking off into the middle distance -- Korda captured the look of a Hollywood leading man. This fit his subject perfectly, as Lawrence Osborne observed in the New York Observer, "Che was the revolutionary as rock star. Korda, as a fashion photographer, sensed that instinctively, and caught it."

The meaning lost -- or not?

Today few people who wear Che clothes or have items with emblazoned the image really know who he was, let alone that it was Korda who took the photo. Che's revolution is history, communism is all-but-dead and, for most people today, Cuba's just another island in the Atlantic. The image has lost its connection to its moment and circumstances, and has become as Darrel Couturie, Korda’s representative, put it, "the image (is) of a very dashing young man."

That dashing young man has a mythic quality that is compelling. His beret links him to the common man, and his faraway look is not unlike that in depictions of the Buddha or Christ. Ironically, Che's daughter Aleida has said that despite the "ubiquitous exploitation" of the image as a fashion statement, it would have made her revolutionary father happy. "He probably would have been delighted to see his face on the breasts of so many beautiful women," she said.

As for the man who captured the iconic image, Alberto Korda died of a heart attack in 2001 while setting up an exhibition of his photographs in Paris. He is buried in Havana.