Beyond ‘Endurance’: The life of ‘Mad’ Frank Hurley, Australian photographer

posted Friday, January 25, 2013 at 6:15 PM EDT

"Hurley is a warrior with his camera, and would go anywhere or do anything to get a picture."

-- Lionel Greenstreet, First Officer of the Expedition Ship Endurance.

"Mad" Frank Hurley was a photographer who by any measure was bigger than life. Compared to him, Mad Max was just an out-of-work traffic cop in a bad neighborhood, and Crocodile Dundee an easygoing suburban barbeque chef.

Born in 1885, in Sydney, Australia, James Francis (Frank) Hurley ran away from school at the age of 13, got a job on the Sydney docks and never looked back. His first camera was a Kodak Brownie that he bought for 15 shillings, which he paid for at the rate of a shilling a week. By 1905, Hurley had gained a reputation for fearlessness, doing anything for a picture. He was famous around Sydney for standing in front of oncoming trains in order to get stunning images. While I am not suggesting that this is a good way to build your portfolio, it's a good example of how Hurley earned the title of "Mad" at a young age.

Aboard the Endurance

Over the next six years, Hurley established himself as a documentary filmmaker and photographer, and in 1911, he joined his first Antarctic expedition. On this trip, he discovered that he loved working under arduous conditions. Returning to Sydney, he assembled the film he had shot into a movie, "Home of the Blizzard." This reality flick was a hit and when explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton saw it, he immediately asked Hurley to join his Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. Hurley signed on at once and was soon loading several tons of photographic gear aboard Shackleton's ship, the Endurance. The expedition planned to be the first to cross the Antarctic via the South Pole, and in August 1914, it set out from England, less than two weeks after the outbreak of World War I.

The ill-fated Endurance, in color.

"Glimpse of the Ship through Hummocks," by Frank Hurley.

Courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales.

The expedition was a disaster. The ship quickly became trapped in the Weddell Sea, Antarctica's huge iceberg filled bay. Shackleton and his 28-man crew stayed with the ship until it was totally crushed by the ice. As the Endurance sank, Hurley repeatedly dove into the icy waters to rescue his glass-plate negatives. Months passed, and finally at the end of the Antarctic winter Shackleton and a few crew members set out in a small skiff to find help. Miraculously, after a journey of 800 nautical miles, they reached a whaling station on South Georgia Island and were able to return and rescue the crew. All 29 men survived.

The Endurance crushed by Antarctic ice.

"The Last of the Ship," by Frank Hurley.

Courtesy of The Ralls Collection.

Frank Hurley photographed the entire misadventure, producing his most famous photographs: A series of images showing the gradual destruction of the Endurance by the pack ice. As always, he was fearless, climbing iced masts, trekking out on the pack ice -- even during the long frigid Polar night -- to get his pictures. Most of Hurley's pictures were black-and-white, glass-plate negatives or black-and-white roll film negatives shot with a Kodak Folding Pocket Camera Model 3A, and a Vest Pocket Kodak that was the only camera retained after Endurance sank

Early color adopter and photo manipulator

But remarkably, Hurley also took color photos on this expedition. He was one of the early adopters of the Paget Process, a color system invented in 1910. It used two glass plates -- one a normal black-and-white glass plate, the other striped with a series of red, green and blue filters, which created a rippled pattern on the black-and-white negative. A glass-plate positive was made from the negative, and when viewed through a similar filter or projected through another, stronger, matrix filter, produced a full color image.

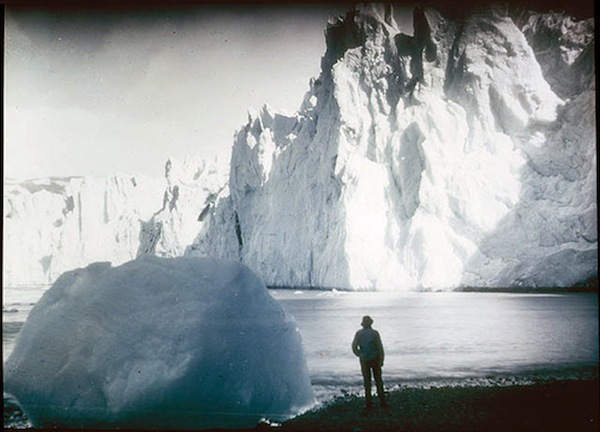

An example of the Paget Process, taken in Antarctica.

"Fortuna Glacier, Elephant Island," by Frank Hurley.

Courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales.

After the rescue in 1916, Hurley traveled to England with his Antarctic photographs and in early 1917 produced another documentary, "In the Grip of the Polar Ice," re-released in 1933 as "Endurance." But he had little chance to enjoy its success. World War I was dragging on, and in August, Hurley joined the all-volunteer Australian Imperial Force as an official photographer with the rank of honorary captain.

Crossing the English Channel, Hurley was shocked by the carnage he found in France and Belgium. However, despite his disgust, he responded to the chaos, saying that the battlefield was "a weird and wonderful sight, with the destruction wildly beautiful."

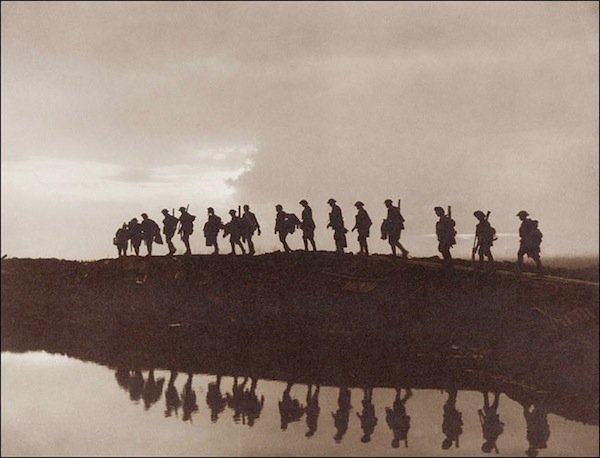

A World War I infantry unit.

"Infantry moving forward to take over the front line at evening," by Frank Hurley.

Courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales.

As usual, he took great risks to get pictures -- but no matter how good the shots were, he was dissatisfied with them. He decided that to truly reflect the chaos and butchery of war, he would make composite images. Starting with a battlefield image, he would add tanks and smoke and a few biplanes, as well. The images were action-packed and powerful, but they got him into trouble with Charles Bean, the official historian of the Australian Imperial Force. Bean called the composites "little short of fake," and refused to allow them to be shown. Protesting what he felt to be censorship, Mad Frank resigned, and only resumed his role after a compromise was reached. Bean allowed six composites to be exhibited in London and Australia, on the condition that they were clearly labeled as such.

A composite image of the Battle of Zonnebeke.

"An episode after the Battle of Zonnebeke," by Frank Hurley.

Courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales.

Love and other adventures

Subsequently, the army sent Hurley to the Middle East, where he was to take aerial photographs of the battle of Jericho. He shot many color images there and decided to smuggle some of them home, rather than turn them over to the army. When he left the Middle East, he took something else back to Sydney. It was a young opera singer he had met in Cairo, Egypt, named Antoinette Rosalind Leighton, who, after a whirlwind 10-day courtship, he had married.

Camels used as ambulances in Palestine, 1918.

"Four camel ambulances attached to the Imperial Camel Corps at Rafa - used as a base for the attack on Gaza," by Frank Hurley.

Courtesy of the Australian War Memorial.

Over the next four decades, Frank Hurley continued to photograph and make movies. There were expeditions to New Guinea and Java, but while several of his films shot after the war were commercially successful, none matched the lasting impact of the Endurance expedition images. Finally, in January of 1962, he came home from an assignment feeling unusually tired and so he sat down in his favorite easy chair to rest. He sat there for a day and a half, and then "Mad" Frank Hurley -- pioneering photographer, adventurer and explorer -- passed away at home.