Aaron Siskind Foundation fellowship winners prove that photography as an art form isn’t dead yet

posted Tuesday, July 23, 2013 at 5:02 PM EDT

Despite all the sound and fury that -- thanks to the ubiquity of cell phone cameras -- real photography is dead and cameras are disappearing, more than 1,450 photographers still applied for the 2013 Aaron Siskind Foundation Individual Photographer's Fellowships. In fact, the work they submitted was so good that the Fellowship jury decided to give out six awards last month rather than the usual five.

The 2013 Aaron Siskind Foundation Fellowship winners are:

- Michelle Frankfurter, a documentary photographer from Takoma Park, Md., for her work on a series of image portraying the journey of undocumented Central American migrants.

- Wayne Lawrence, a portrait photographer from Brooklyn, New York, for his documentation of African-American Orthodox Jews living in New York City.

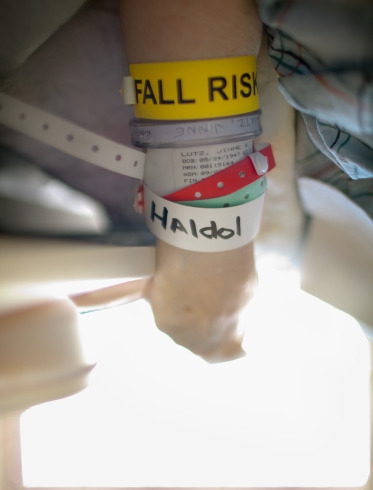

- Joshua Lutz, a conceptual photographer from Katonah, NY, for his conceptual portrait of his mother's descent into mental illness.

- Justin Maxon, a documentary photographer from Eureka, Calif., for his work to capture life in Chester, Pa., where unemployment, murder, corruption and racism are high.

- Jenny Riffle, a fine-art photographer from Seattle, Wash., for her portraits of Riley, a child who wanted to live the mythic life of Mark Twain adventurers Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn.

- Sasha Rudensky, a fine-art photographer from New Haven, Conn., for documenting an orphan generation of Russians, Ukrainians and Belorussians that have disowned their past and are struggling to find their identities in the present.

Photo by Michelle Frankfurter

Such excitement and photographic energy would have made Aaron Siskind very happy. Born in New York, Siskind began taking pictures after he received a camera as a wedding gift. In the 1930s, he produced several series of social documentary images but found that his real interest was in abstract images of nature and architecture. To pay the bills, Siskind worked as a teacher in the New York City school system until 1950, when he met the photographer Harry Callahan who invited Siskind to teach photography at the Illinois Institute of Technology's Institute of Design in Chicago. After a long and successful career, Siskind died in 1991 leaving the Foundation as his legacy to future generations of photographers.

Photo by Wayne Lawrence

Charles Traub, president of the Aaron Siskind Foundation and chair of the MFA Photography, Video and Related Media Department at New York City's School of Visual Arts, told Time magazine that Siskind "was a wonderful teacher; he was always interested in new ideas and in things that challenged us. We're interested in all aspects of the creative photographic medium and all genres of photograph investigation -- as long as the work is new and fresh."

Photo by Joshua Lutz

I like new and fresh because it goes against the notion that there is nothing new to say in photography. The idea of the Siskind Fellowships is to support innovative and interesting work, and consequently the eligibility requirements are rather wide open. Applying for a Fellowship is open to virtually any working photographer who is a U.S. citizen or resident and demonstrates a serious commitment to photography. Their applications are judged on "the basis of artistic excellence... and the promise of future achievement in its widest sense."

Photo by Justin Maxon

The marvelous thing about these grants is that they are awarded solely on the photographic work submitted. The jury looks at the portfolios and nothing else -- not the photographers' credentials, professional references or age. This year's judges were Natalie Matutschovsky, senior photo editor at Time magazine, photographer Andrew Moore, who recently published a new book on Cuba, and Tim Wride, curator at the Norton Museum of Art. This year's Fellowships winners will receive $8,000 each to pursue their projects. They come from all over the nation and their projects, as you've seen, are very diverse and innovative.

Photo by Jenny Riffle

Grants and fellowships like the ones the Aaron Siskind Foundation provides have become a resource for young and not-so-young photographers to pursue projects outside commercial photography. For me and many other photographers, these self-assigned projects are at the heart of what keeps photography relevant and important today.

Photo by Sasha Rudensky