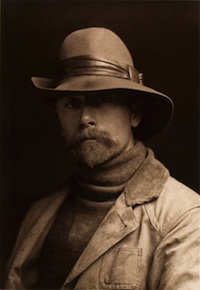

Shadow Catcher: The life and times of Edward Curtis, legendary photographer of ‘The North American Indian’

posted Friday, October 4, 2013 at 8:48 AM EDT

Yesterday, Christie's auction house was set to sell a collection of 20 photographic portfolios that make up the monumental work, "The North American Indian," by photographer Edward S. Curtis. Christie's estimates that these photogravure portfolios and the complementary sets of 20 descriptive texts would go for as high as $1.5 million. (Update: We found out that it did not sell, though a similar auction lot back in April 2012 sold for more than $2 million.)

These portfolios are the result of one of the earliest and largest ethnological projects ever undertaken. It's a story that spans the North American continent, involves several Native American tribes and includes a cast of characters ranging from the likes of banker J.P. Morgan to film director Cecil B. DeMille to United States President Theodore Roosevelt.

Expeditions of a restless youth

Edward Curtis was born in rural Wisconsin in 1868, but in 1874 he and his family moved to Minnesota where his grandfather ran a grocery. But Curtis was no shopkeeper, and the restless young man left school in the sixth grade and, in 1885, became an apprentice photographer in a portrait studio in St. Paul. Two years later when the family moved to Seattle, Curtis purchased a camera and became a partner in a local photographic studio there.

In 1895, Curtis met Princess Angeline, the daughter of Chief Sealth (Seattle), the leader of one of the groups of Coast Salish people who had lived in the Seattle area long before the first white settlers arrived in 1851. He photographed the 95-year-old Angeline, and two of his photos were accepted and hung in the National Photographic Society exhibition of 1898.

Princess Angeline, 1896

Photo by Edward S. Curtis

That year he also had a chance encounter with a group of scientists while he was photographing on Mt. Rainier. One of them, George Bird Grinnell, was an expert on Native Americans and by the next year Grinnell had taken Curtis on as the official photographer for his Harriman Alaska Expedition. Impressed by his work on that expedition, as well as his desire to learn about the native people, Grinnell then invited Curtis to be the photographer on his next expedition to study the Blackfeet tribe of Montana in 1900.

Photo by Edward S. Curtis

Photographing 'The North American Indian'

Curtis became fascinated by the North American Indians and began to seek funds for a giant project to document them before they disappeared. As he later wrote in the introduction to his seminal work, "The information that is to be gathered... respecting the mode of life of one of the great races of mankind must be collected at once or the opportunity will be lost."

He pursued funding and, in 1906, the financier J.P. Morgan gave Curtis $75,000 to carry out the project. But there were strings attached. According to the Morgan agreement, the money was to fund fieldwork for five years and Curtis was to receive no salary. Additionally, Morgan was to receive 25 sets of 20 portfolios and 500 original prints. Curtis accepted these terms, although as it turned out, he ended up working on the "North American Indian" for 20 years.

Photo by Edward S. Curtis

This monumental effort often required Curtis to be absent from home for months on end, and took its toll on his marriage. In 1919, his wife Clara, who had been left to manage both their large family and his studio, divorced him. In the settlement, Clara got the studio and its collection of glass-plate negatives. However, rather than see her have them, Curtis and his daughter Beth went to the studio and destroyed most of the glass plate negatives there.

Photo by Edward S. Curtis

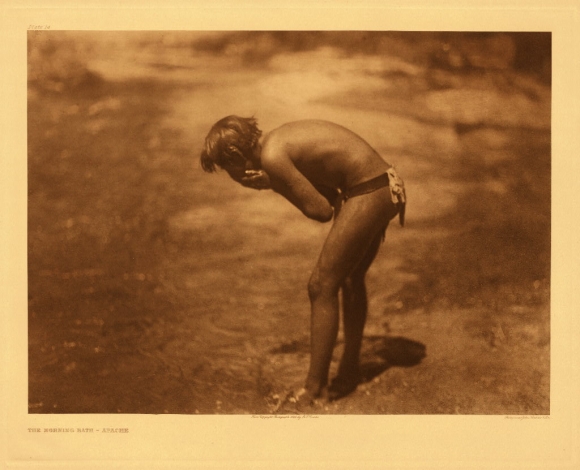

A foray into film

While primarily shooting still photographs, Curtis made a point of making wax cylinder recordings and motion pictures of native people, too. In 1912, he got the idea to produce a feature length movie and recruited the Kwakiutl tribe, who live on the rugged, rain swept Charlotte Islands off the coast of British Columbia, to be his cast. The film tells the story of a traditional Kwakiutl "potlatch," an over-the-top, days-long gift giving party, where the person who gives away the most and best gifts is the winner. This extraordinary 1914 silent epic is filled with costumed dancers, masked shamans, gorgeous carved wooden boats and decorated native long houses. Released with the rather lurid title, "In the Land of the Head-Hunters," it made less than $3,300 in its first run, despite critical praise.

Photo by Edward S. Curtis

Curtis opened a new photo studio in Los Angeles in 1922, along with his daughter. But, as usual, he was short of cash. To make ends meet, he worked as an assistant cameraman for Cecil B. DeMille on the 1923 filming of the original, silent "Ten Commandments" motion picture. But even with this work, he still needed money and, in 1924, he sold the master print, original camera negative and rights to "Head-Hunters" to the American Museum of Natural History. He was paid $1,500 for a film that had cost him $20,000 to make.

Photo by Edward S. Curtis

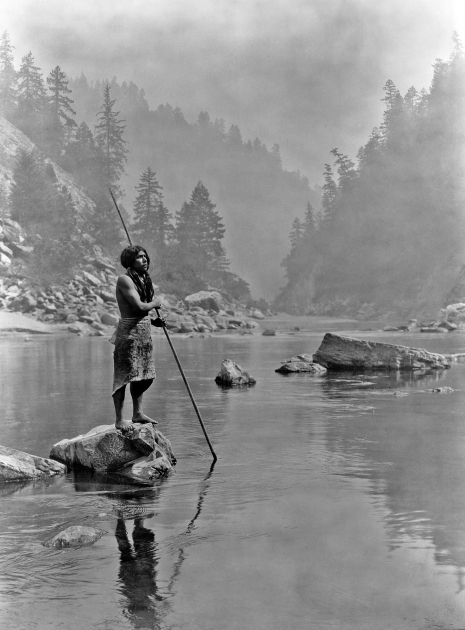

Staging the vanishing Wild West

Curtis was an excellent photographer and like his contemporary, Buffalo Bill Cody, he was a showman, too. By the beginning of the 20th century, when both men were the most active, the American West they depicted no longer existed -- the frontier was gone. The huge herds of buffalo had been decimated and the Native American peoples were mostly confined to reservations. Yet the dream of the Wild West, with its wide open spaces and "natural" Native Americans remained a powerful draw for the denizens of the crowded, smoke filled, industrial cities of the American Northeast and of Europe.

Photo by Edward S. Curtis

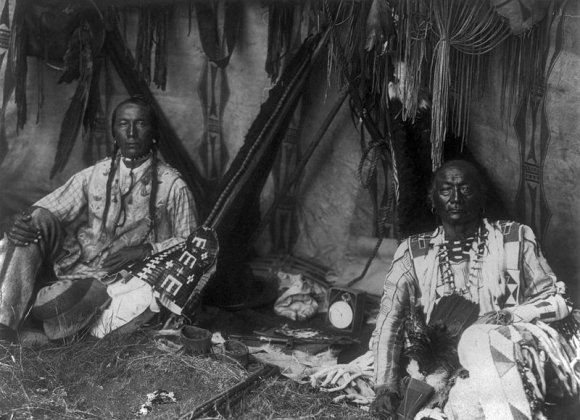

Cody and Curtis saw themselves as educators and entertainers. Curtis was not a documentarian in our modern sense. There were few decisive moments. He would contrive images, asking people to dress up like their grandparents for the camera. He would have them pose and rearrange objects to his liking. For instance, in one photo of two seated men, he retouched out of the picture the clock that was between them.

Photos by Edward S. Curtis

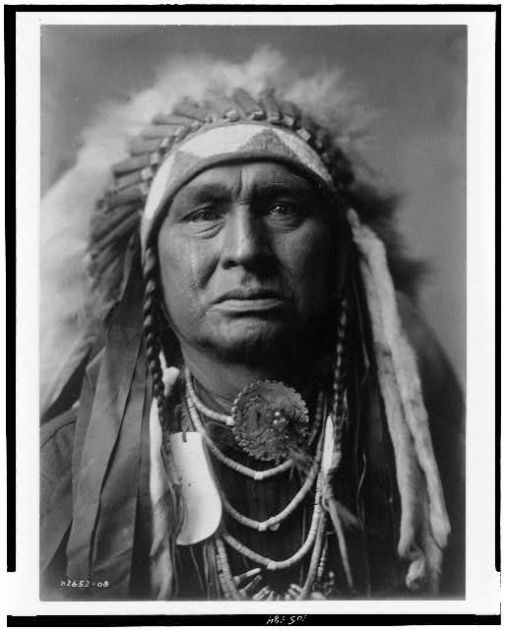

The legacy of 'The North American Indian'

The rights to "The North American Indian" belonged to J.P. Morgan, and in 1935 his estate sold thousands of individual paper prints, the copper printing plates, the unbound printed pages, the original glass-plate negatives and 19 complete bound sets of portfolios to the Charles E. Lauriat Book Company of Boston for $1,500. Lauriat bound the loose printed pages, and sold them along with the completed sets. The rest of the material, including 285,000 photogravure prints and original copper printing plates remained untouched in the bookseller's Boston basement. They were not rediscovered until 1972.

The Christie's collection contains not only the 20 photographic portfolios, but also the 20 descriptive texts that go with them. Curtis diligently took notes about everything he did and saw as he went about recording the lives of native people. He produced some 40,000 photographic images of over 80 native groups as well as over 10,000 wax cylinder recordings of tribal languages and music.

Despite his reenactments, his posed shots and the erasure of modern objects from the images, Curtis's work remains the most complete collection of material about the first people to live on the continent of North America.

Photo by Edward S. Curtis

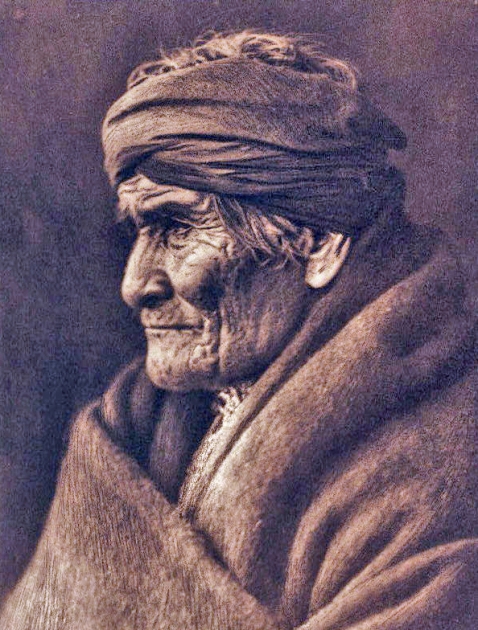

As his great supporter Teddy Roosevelt wrote, "In Mr. Curtis we have both an artist and a trained observer, whose work has far more than mere accuracy, because it is truthful... Mr. Curtis in publishing this book is rendering a real and great service; a service not only to our own people, but to the world of scholarship everywhere."

For the Native Americans, who were wary of anything involving the white peoples, he was unusual -- in his dealing with them he was straightforward and honest. Over the years as he traveled among the tribes, he not only won their respect and affection, but he acquired a native name. To them he was simply "The Shadow Catcher."

Photo by Edward S. Curtis